Blog Post

An Ancient Historian at the Movies

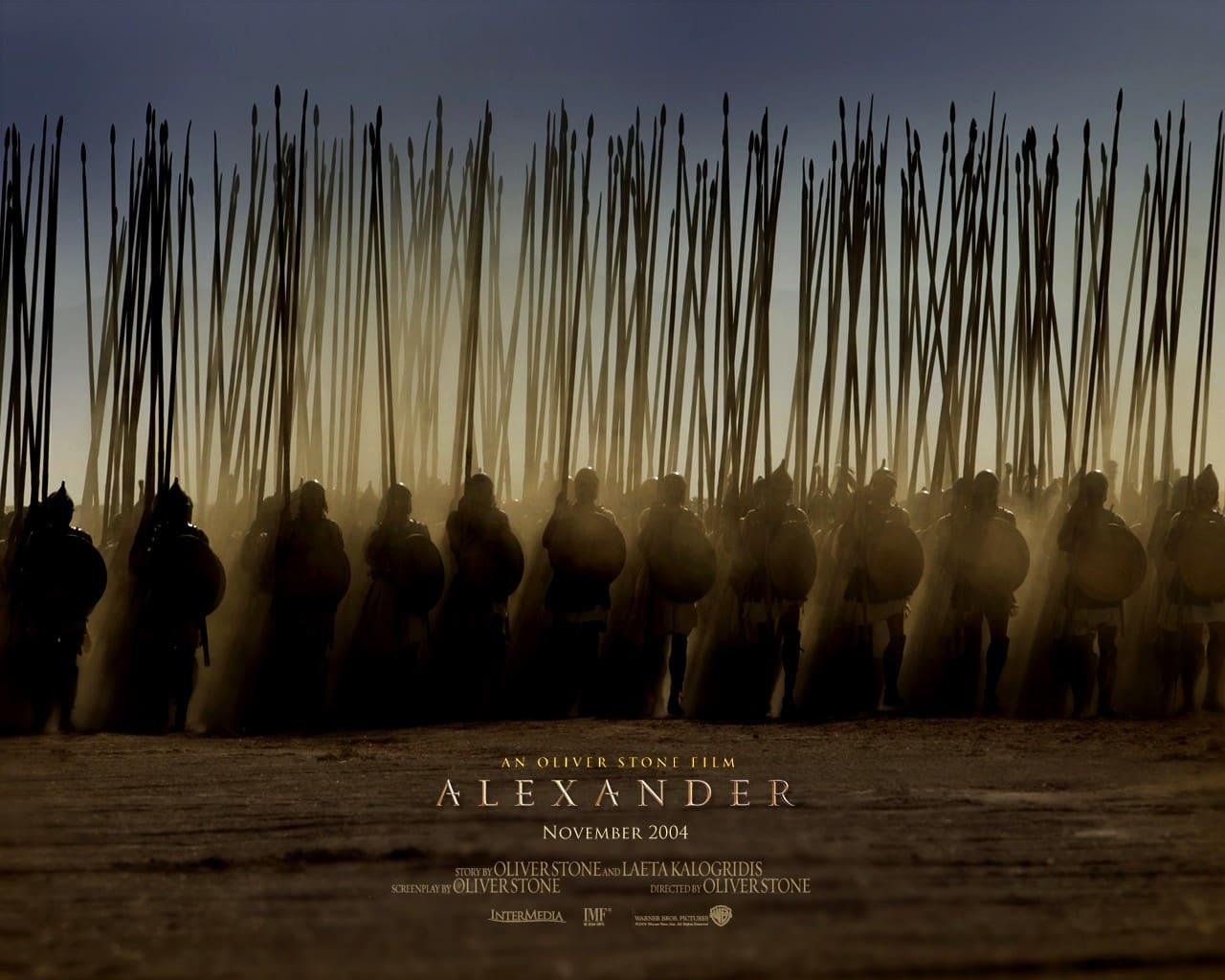

My path to academia did not start with a call to the noble pursuit of diligent scholarship, nor with a dream of one day teaching at a venerable institution like the University of Oxford. It started with movies. Like so many of my generation, I was drawn to the history of the Greeks and Romans by the historical blockbusters of the early 2000s: Gladiator (2000), Troy (2004), Alexander (2004). There were also shows like HBO’s Rome (2005-2007), computer games like Age of Empires (1997-2005) and Rome: Total War (2003). In my formative years, a mass of popular culture put versions of ancient history on display, and I started wondering: how much do we really know about this world? What is all this spectacle really based on?

It was BBC’s Time Commanders (2003-2005) - a game show in which contestants reenacted ancient battles using the Rome: Total War game engine and graphics - that turned my attention to Greek and Roman warfare. As a high school student in the Netherlands, I was glued to the screen, straining to follow as much as I could without subtitles, probably missing half of it. From then on, I was hooked on ancient military history. When, as a History student at Leiden University, I had the chance to take a course on Greek Warfare, my path was set.

As an overconfident undergraduate, I believed I already had the authority to criticise movies and games when they got things wrong. I made a nuisance of myself to family and friends with my rants about what these works should have done differently. I was no expert of anything at the time. But with the completion of my PhD in Classical Greek warfare (UCL, 2015) and the years of research and teaching I have done since, my understanding of historical authenticity has come to be grounded in familiarity with the primary sources and the centuries of scholarship that have shaped the way we make sense of the ancient world. And so, when I was invited to comment on ancient warfare scenes in movies for Insider’s YouTube series How Real Is It?, I jumped at the chance. Here was an opportunity to play the part I had wanted to play since the start of my academic journey, and to revisit my own question – what is this all based on? – for the benefit of anyone who may have been asking themselves the same thing.

The How Real Is It? concept is simple: scholars and professionals (from astronomers to weaponsmiths) are presented with ways in which their area of expertise has been portrayed in film and TV, and asked to comment on what is and is not accurate. The downside of this format is that it tends to accentuate the negative; the expert is not asked to give due consideration to moviemakers’ intentions and limitations or to the quality of a film as a piece of entertainment. Insider’s editors are constrained by the site’s dynamics and generally see more value in a quick and harsh verdict than a generous one. Experts aren’t asked to provide constructive criticism but to pick out errors – not all of them consciously made and not all of them preventable. But the upside is that it links academic knowledge directly with wider audiences’ main form of access to the subject. Most people understandably know little more about the ancient Greeks and Romans than what they learned in school and what they saw in films like Gladiator or 300 (2007). Even when they understand perfectly well that these movies aren’t meant to be taken as history lessons, much of what they see still seeps into ‘common knowledge’ about what the ancient world was like. Even the portrayal of premodern life in fantasy settings like Lord of the Rings (2001-2003) or Ga ame of Thrones (2011-2019) has influenced people’s picture of the past. Talking about these movies and shows allows a historian to meet people where they are, but also to address myths and misconceptions at their source.

What do movies get wrong about ancient warfare, in particular? The common theme of my comments is that they skip over the mundane and the practical in the pursuit of spectacle. Battles are usually portrayed as chaotic brawls with outrageous casualty rates; movies disregard the importance of unit cohesion and ignore that the vast majority of warriors involved in such engagements would stand well back from the cutting edge and rarely participate in the bloodshed. The focus of battle scenes is typically on distinct individual fights that allow the heroes’ martial prowess to shine. If there is any unit action, it is to show off whatever unnecessarily complicated manoeuvres the extras have been drilled to perform, which usually have no bearing on the simple and straightforward drill of ancient infantry. The visual allure of fire and explosions drives movie makers to introduce these flashy features to battle scenes wherever they can, despite their rarity in the historical record and at the expense of the boring but practical use of ordinary rocks. The need to speed up the action means that cities and forts in movies are usually suspiciously easy to attack; there is hardly ever room for historically common defensive obstacles like the humble ditch.

Perhaps we should expect no more of movies. They are entertainment, after all; they have no obligation to accuracy. But it is possible to create ancient battle scenes that are both engrossing and faithful to historical sources. Oliver Stone’s Alexander, for all its faults, presents the battle of Gaugamela (330 BC) in a way that allows the viewer to understand exactly how Alexander the Great defeated Darius III, with painstaking attention to authenticity of equipment and tactics but without making any concessions to the fury and excitement of the clash.

In my video for Insider, I tried to stress that this should be the example to follow. Whether any directors will pick this up is an open question. My comments are not historical consultation; ‘Expert Reacts’-type videos are themselves a form of entertainment, not an attempt to hold creative industries to account. As the expert, I am just bringing together two things I love – historical films and the study of ancient warfare – and feeding back what I have learned over the years to an audience that might never otherwise find out how a subject expert sees these movies. The platform offered by Insider has allowed me to reach far more people than I ever could have hoped for. It has been a privilege to see this work resonate with millions of viewers, some of whom now remind me of my repeated point about the importance of ditches wherever I show my face online (and occasionally in real life). I never expected that I would find such an audience as an ancient historian. But it is perhaps not surprising that I should find this audience at the very intersection of history and entertainment that got me interested in antiquity in the first place.

Lincoln has been hugely supportive of the public engagement work I do alongside my other academic responsibilities. There is real recognition here of the value of communicating humanities research beyond the academy, and a real appreciation of the effort that goes into rethinking and reshaping such research to send a clear message across different media, from popular history magazines to online community forums, podcasts and YouTube videos. I have continued to work with a variety of platforms since that first invitation from Insider, and I hope to continue doing so until I run out of things to say.