Historic Lincoln

Discover Items from Our Senior Library & Archive

To celebrate our anniversary year in 2027, we have selected 20 items from the Senior Library and 27 from the Archives to share online.

Senior library

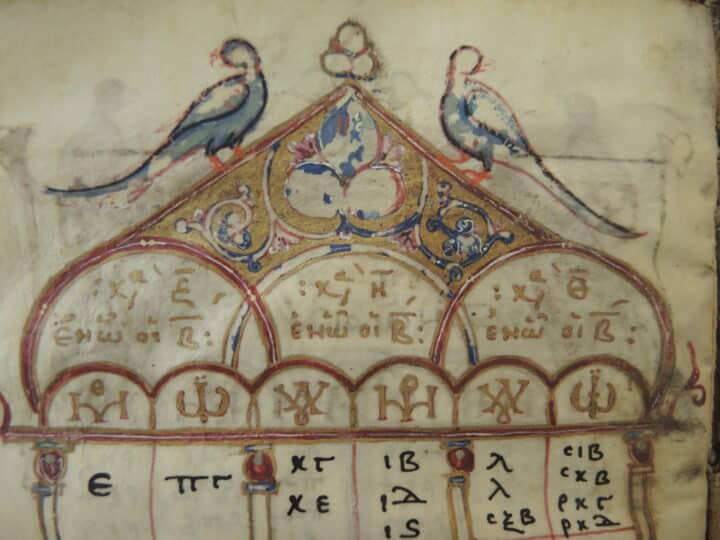

The beginnings of the College library: Thomas Netter, Doctrinale

Thomas Netter (d.1430) was an English theologian whose major work, the Doctrinale, is a defence of Catholic dogma and rituals, written in response to the attacks of Wyclif and his followers. The work itself is austerely orthodox but the manuscript pictured here, one of several given by Richard Fleming, the College’s founder, offsets the text with its beautiful illuminations. Together these conjure a sense of the spiritual emphases of the Founder and his hopes for the College.

senior library

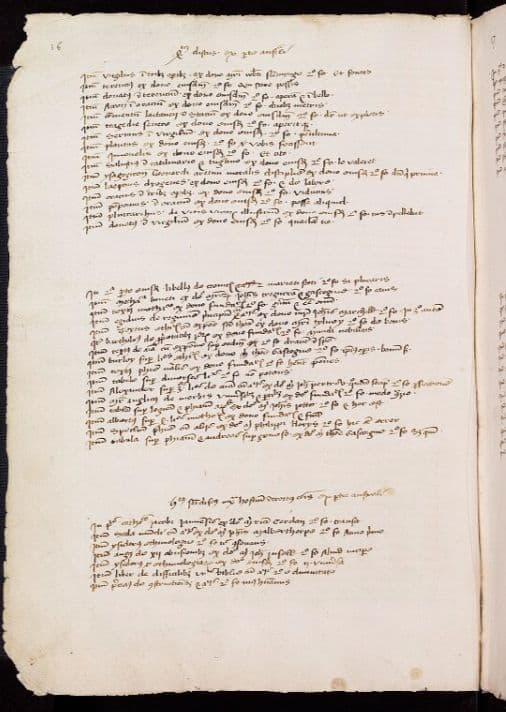

The earliest catalogue of the College library

The earliest list of books in the College library is recorded in the Vetus registrum. It is strictly not a catalogue but an inventory, made in 1474 at the request of Thomas Rotheram, Bishop of Lincoln, as part of a College valuation. The manuscripts are listed by shelf (or press), with books arranged by subject, making it possible to reconstruct the 15th century library in some detail: starting on the south side of the room with Bibles, through ecclesiastical history, classical and humanist works to theology, all in a large bright room with mullioned windows on both sides.

senior library

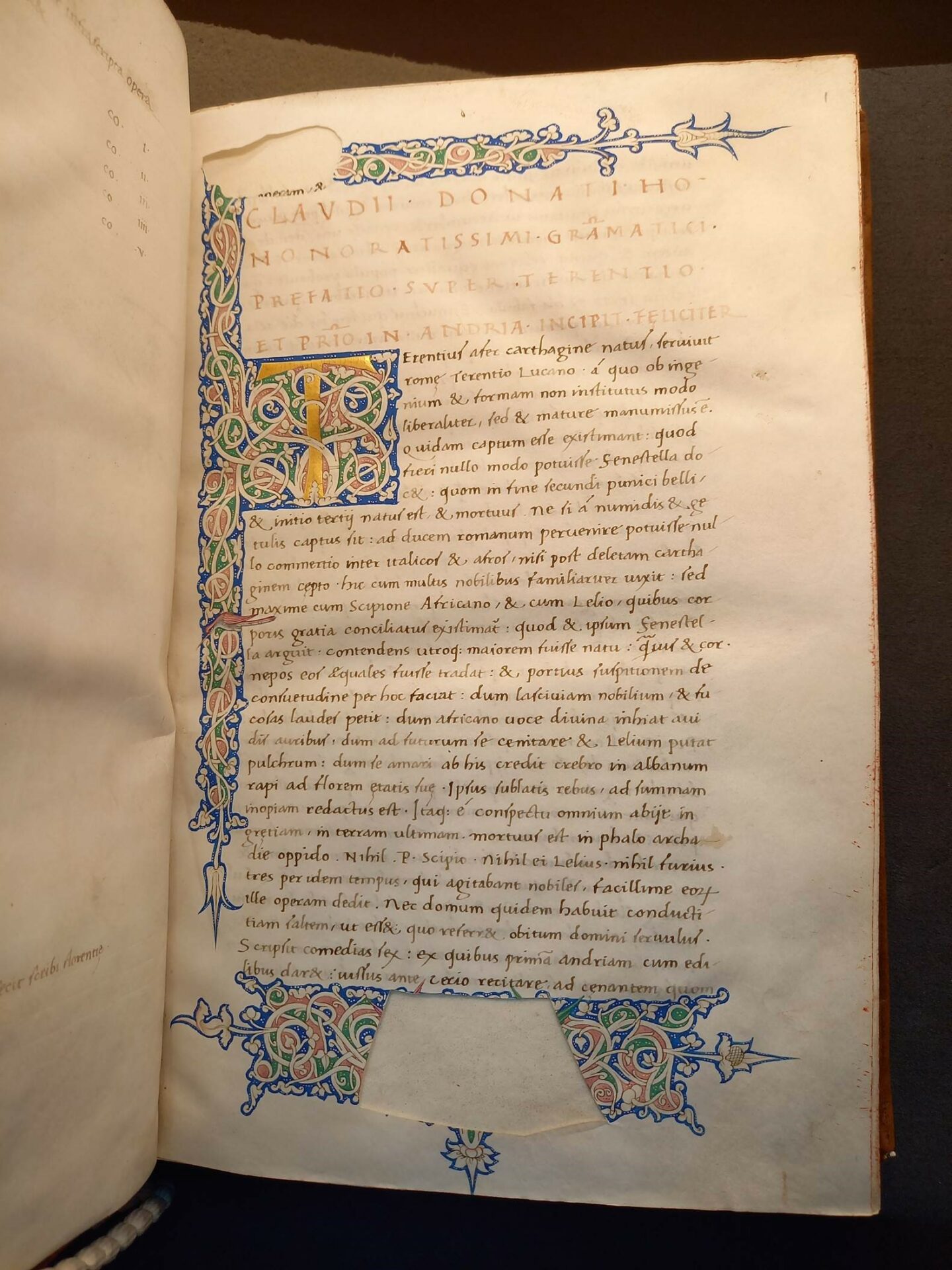

Book buying in 15th century Florence

This 15th century copy of a 4th century commentary on the plays of the Roman playwright Terence was given by the Founder’s nephew, Robert Fleming (d.1483). Classical works like this were an important part of Fleming’s library and because of this he is considered to be one of the earliest English humanists. While many of Fleming’s manuscripts have been described as workaday, this manuscript, with its fine illuminations, is part of a small group of 15th century Florentine manuscripts bought by Fleming on his travels in Italy from the celebrated bookseller Vespasiano da Bisticci.

senior library

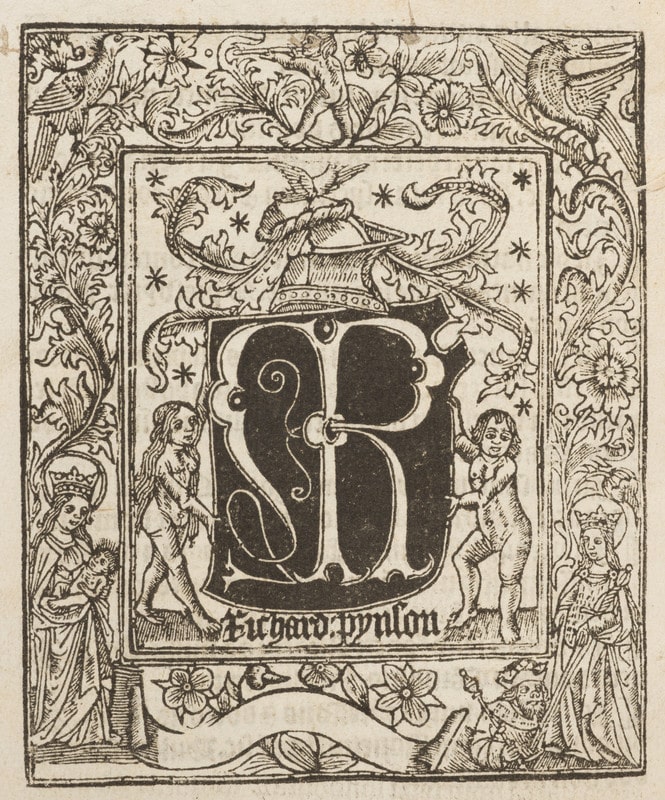

The world of the book in early Tudor England

This small book, a religious work entitled Directorium sacerdotum ad usum Sarum, was printed in London in 1498 by the English printer Richard Pynson, whose printed device is pictured here. The original binding, still intact, was made by an Antwerp binder working in Cambridge in the 1490s: while we don’t know his name, he can be identified by the stamps (or “tools”) used to decorate the binding. The book then made its way to Oxford, into the hands of Robert Field, a Fellow of Lincoln and College Bursar who died in 1521. Like generations of readers he has inscribed the book with his name: Iste liber est Roberti Fyld.

Senior library

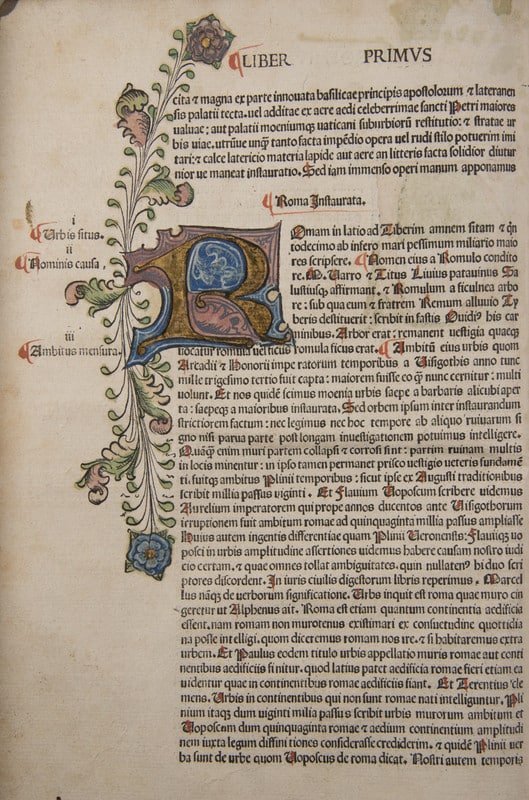

The library moves with the times: a 16th century donation

In around 1518, Edmund Audley, Bishop of Salisbury, gave Lincoln its first major donation of printed books. At this point, the library – one of the best in Oxford – would have been made up almost entirely of manuscripts. Audley’s donation of printed books would have ushered the College library into the modern age of print. Produced in the major printing centres of 15th century Europe, and illuminated and bound by both Continental and English craftsmen, the books included in Audley’s donation represent the way in which the European trade in printed books broadened the horizons of Oxford libraries. These books were, and continue to be, an important part of the College library.

senior Library

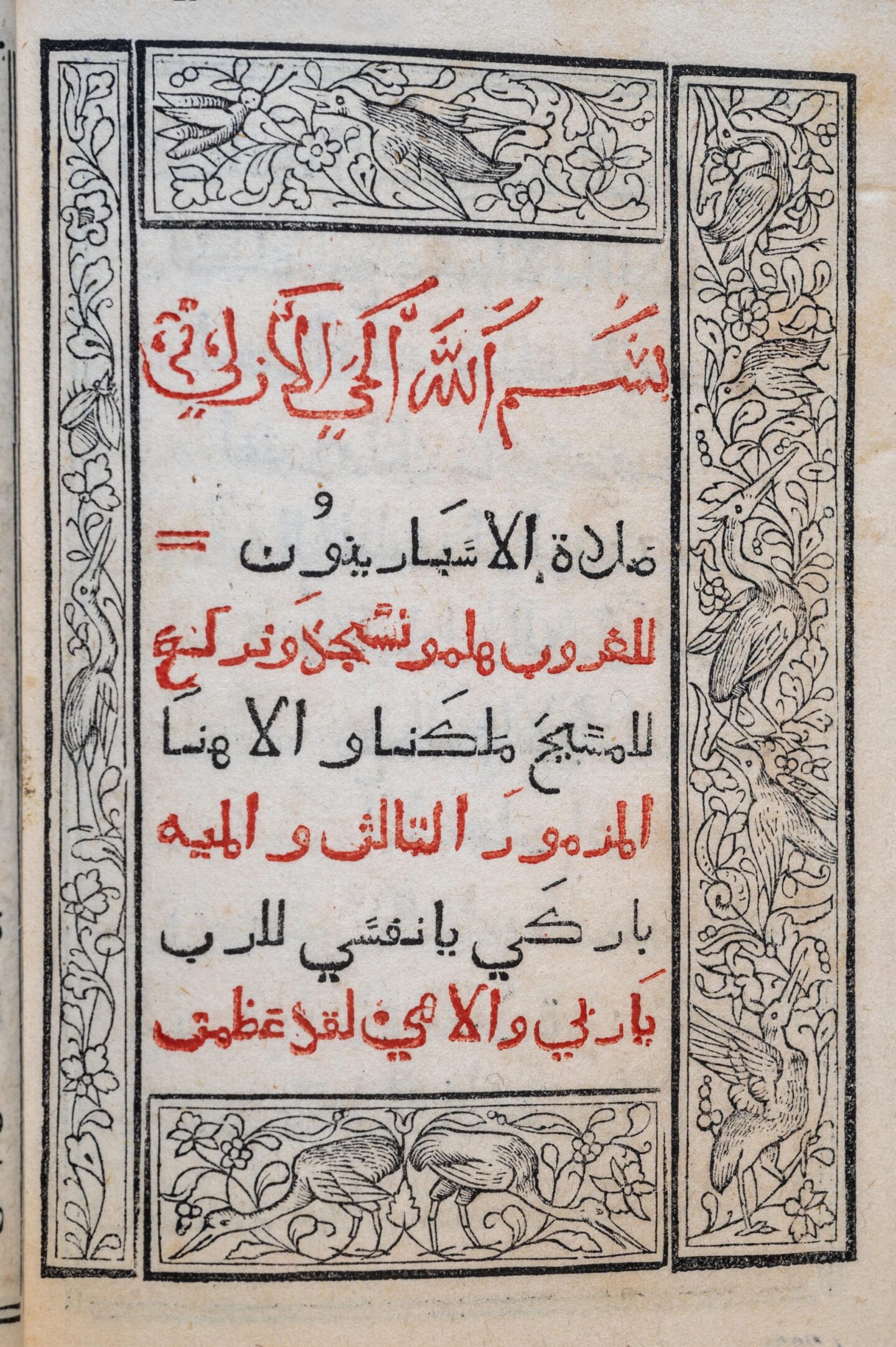

Kitāb ṣalāt al-sawā'ī: an Arabic book of hours

The first book printed in Arabic in moveable type, this important edition was printed in Italy in 1517 and includes an Arabic translation of the Psalms done by Abdallah Ibn al-Fadl al-Antakl, a theologian and translator active in Antioch in the 11th century. Printed in red and black in an elegant type with ligatures and vocalisation marks, the text is set within a series of woodcut borders. Some of these are in an arabesque design of vines, leaves and flowers; others are scattered with the repeated image of a bird with the long legs, neck and beak of an ibis.

senior library

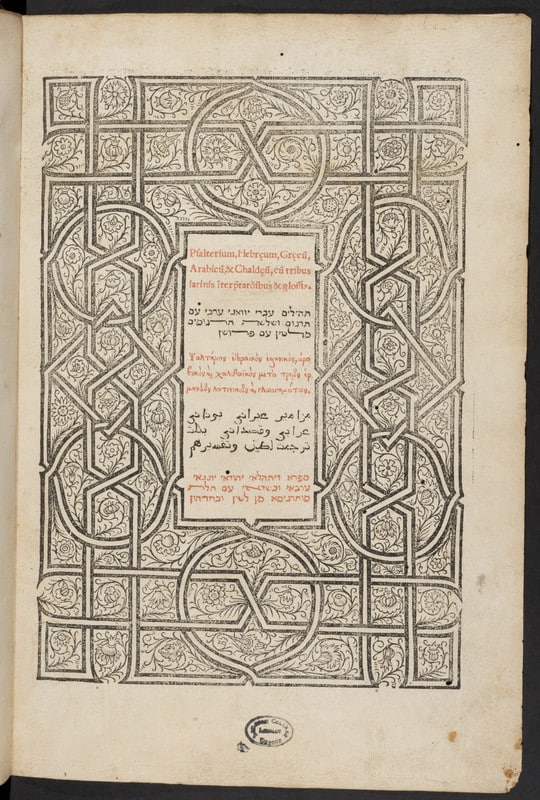

An early account of Christopher Columbus

The Genoa Psalter, printed in 1516, was the first polyglot printing of any part of Bible. The Psalms are laid out in 8 columns: Hebrew, a Latin paraphrase, the Vulgate Latin, Septuagint Greek, Arabic, and Aramaic (with a Latin paraphrase). These columns are surrounded, and at times overwhelmed, by editor’s notes. In the notes to a verse of Psalm XIX (“their words go out to the end of the world”) can be found the first biographical sketch of Columbus, who was a native of Genoa where the book was printed, and the first published account of his second voyage.

senior library

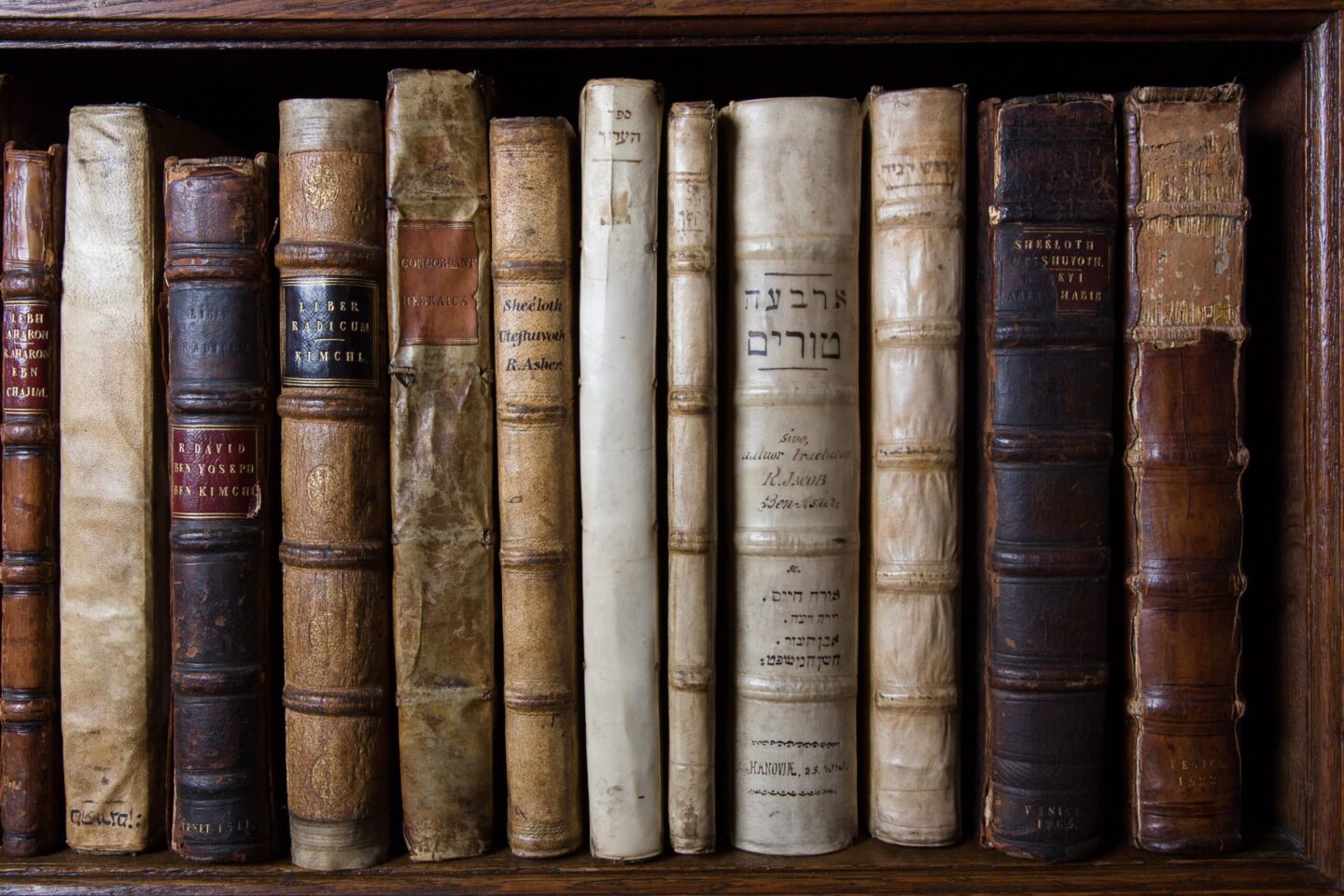

Hebraica from the library of a Lincoln Rector

Richard Kilbye (1560-1620) was Rector of Lincoln from 1590 until his death and one of the translators of the King James Bible, printed in 1611. His library, which he left to the College, included Hebrew bibles and commentaries, all important for the scholarly work involved in a translation which is still considered to be one of the most important books in the English language. Some of these volumes, like this edition of the Toledot Aharon (an index to the Talmud by the 16th century Italian Talmudist Aaron of Pesaro) printed in Germany in 1586, contain manuscript annotations in Kilbye’s neat Hebrew hand, showing his detailed study of these texts.

senior library

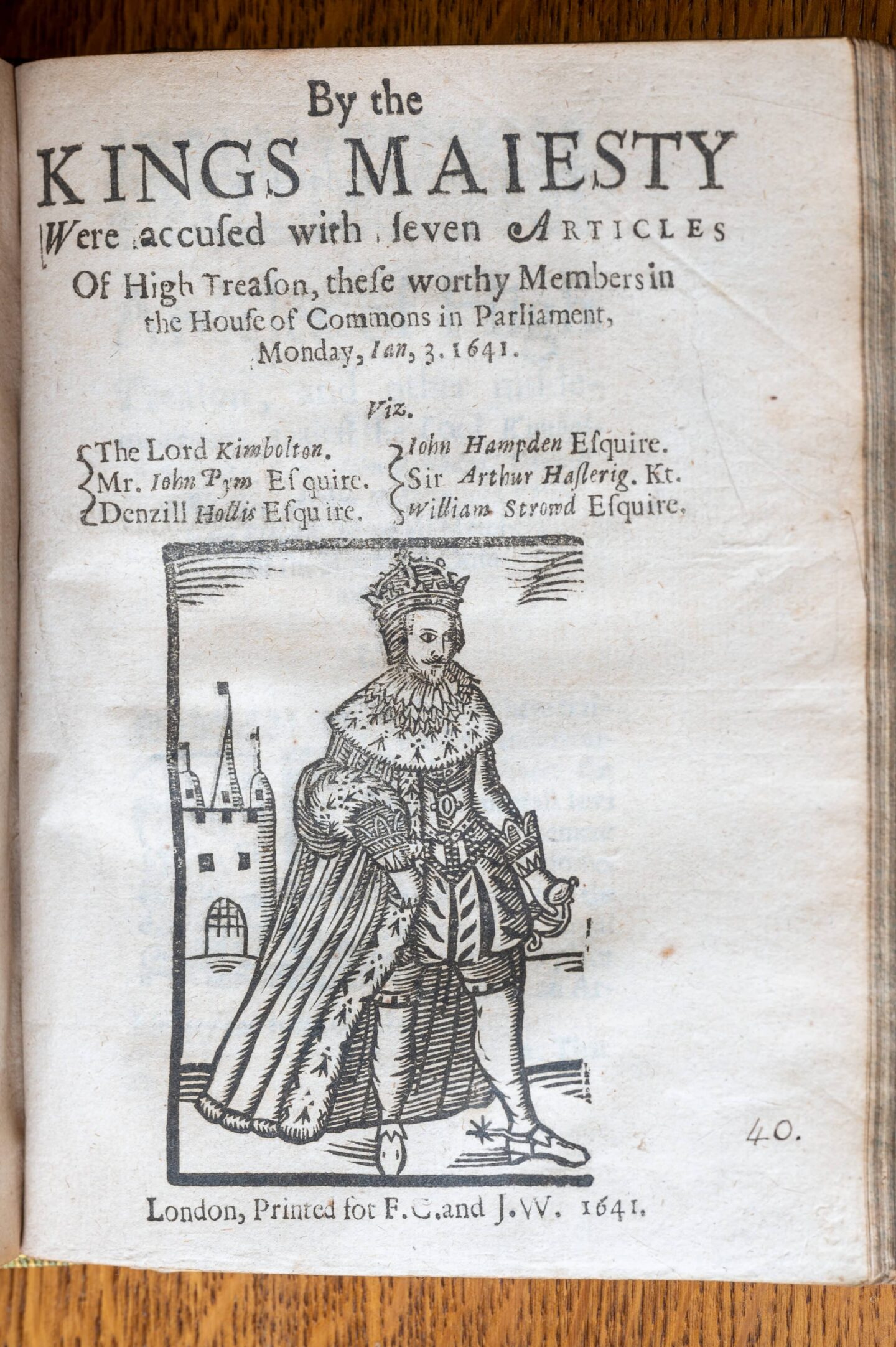

Civil War pamphlets

The 77 volumes of pamphlets left to the College by Rector Thomas Marshall (d.1685) are one of the most important, and remarkable, collections in the Senior Library. Contemporary collections of English Civil War material are rare and these volumes are a rich resource for our understanding of printed ephemera in the period.

The majority of the pamphlets relate to the religious and political events of the Civil War: letters, sermons, speeches, royal proclamations, parliamentary orders, and political and religious propaganda. The volumes also include pamphlets from the reigns of Elizabeth and James I, among them tracts on English colonisation and religious conditions in the New World.

senior library

A 12th century Greek manuscript and a 17th century traveller

The clergyman, traveller, amateur botanist and Lincoln alumnus George Wheler (1651-1724) gave the College an important collection of manuscripts which he had bought on his travels in Greece and the Levant in 1698. Among them was this 12th century manuscript of the Greek Gospels, written on parchment and in a 15th century Greek or Byzantine binding of wooden boards covered in red silk velvet. Wheler was not only interested in manuscripts: he returned from Greece with marbles and inscriptions he had bought in Athens, a collection of coins, and plants (including St John’s Wort) which had not previously been cultivated in this country.

senior library

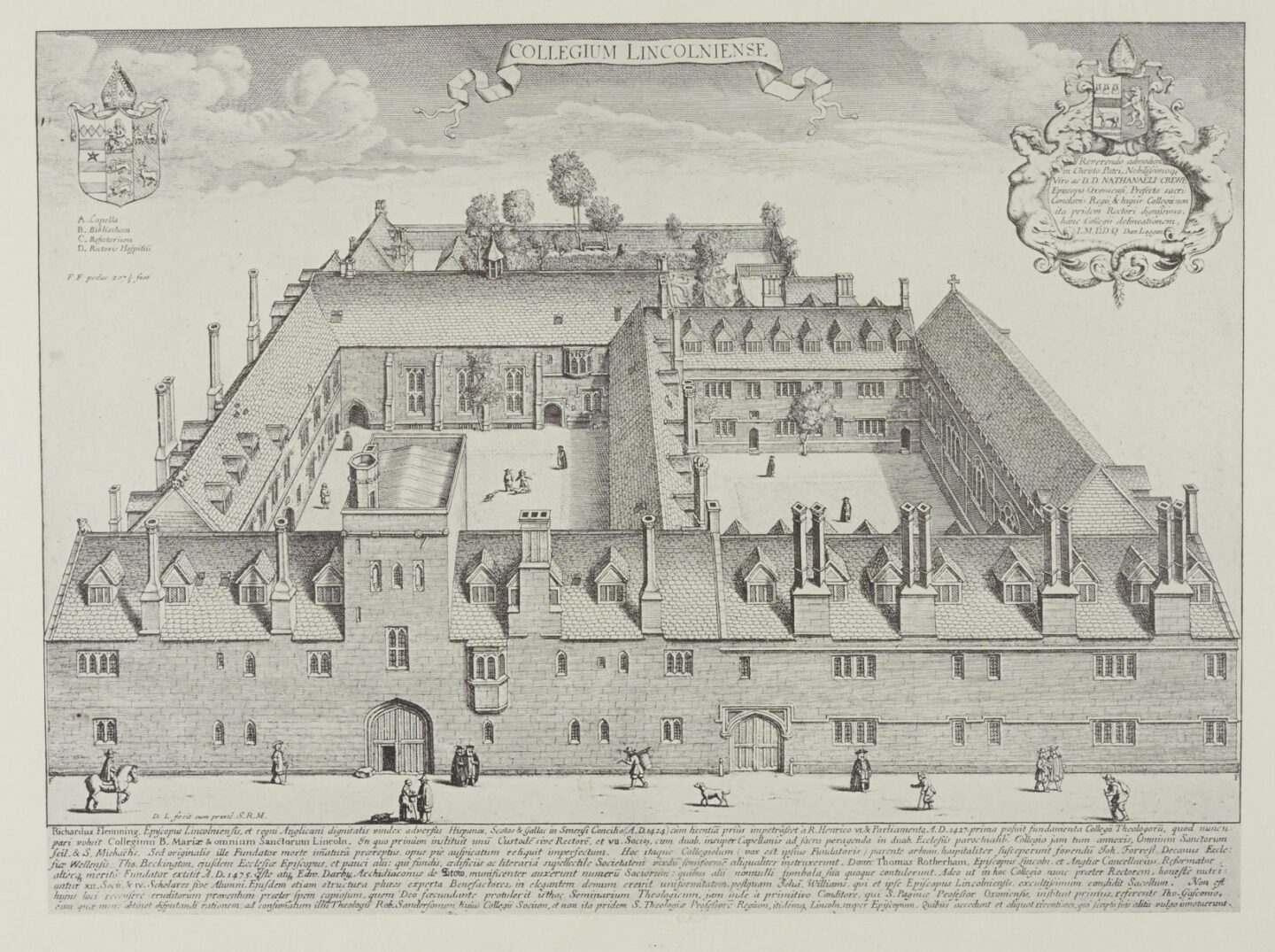

A bird’s eye view of 17th century Lincoln

In around 1660, Charles II commissioned the engraver David Loggan to produce drawings of the Oxford colleges: Loggan’s collection of copperplate engravings, the Oxonia illustrata, was published in 1675 to celebrate the restoration of Charles II to the throne. Lincoln’s copy, for which it paid the author 30 shillings in 1675, is in a fine red goatskin (morocco) binding with the University arms stamped in gilt on the covers. If you look carefully you can see a dog in Front Quad: this would now be a breach of College rules!

senior library

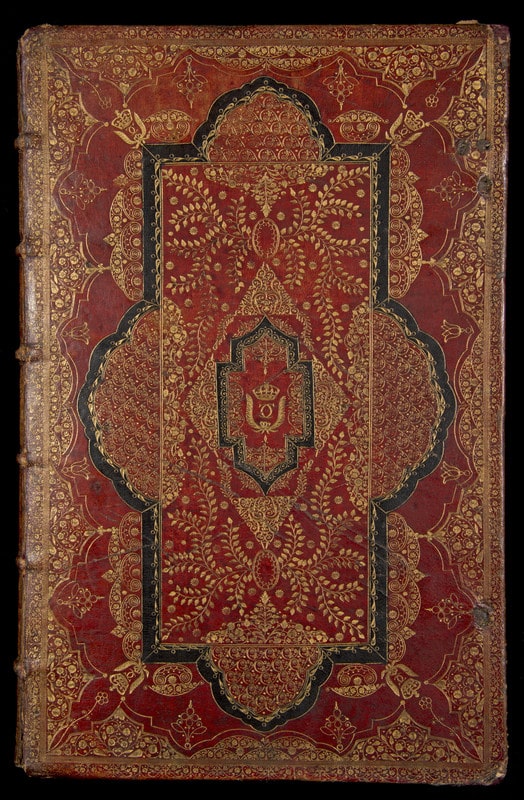

A binding for Charles II and the Chapel Royal

This copy of The Book of Common Prayer was presented to the College by Nathaniel, Lord Crewe, in 1674 and came originally from the Chapel Royal. The splendid binding is by Samuel Mearne, the greatest bookbinder of the English Restoration. The volume is decorated in Mearne’s characteristic style: sprays of gilt-tooled flowers and leaves against a backdrop of red goatskin (morocco) and black inlay. The covers and edges of the book are also decorated with the King’s cipher (CC) and crest.

senior library

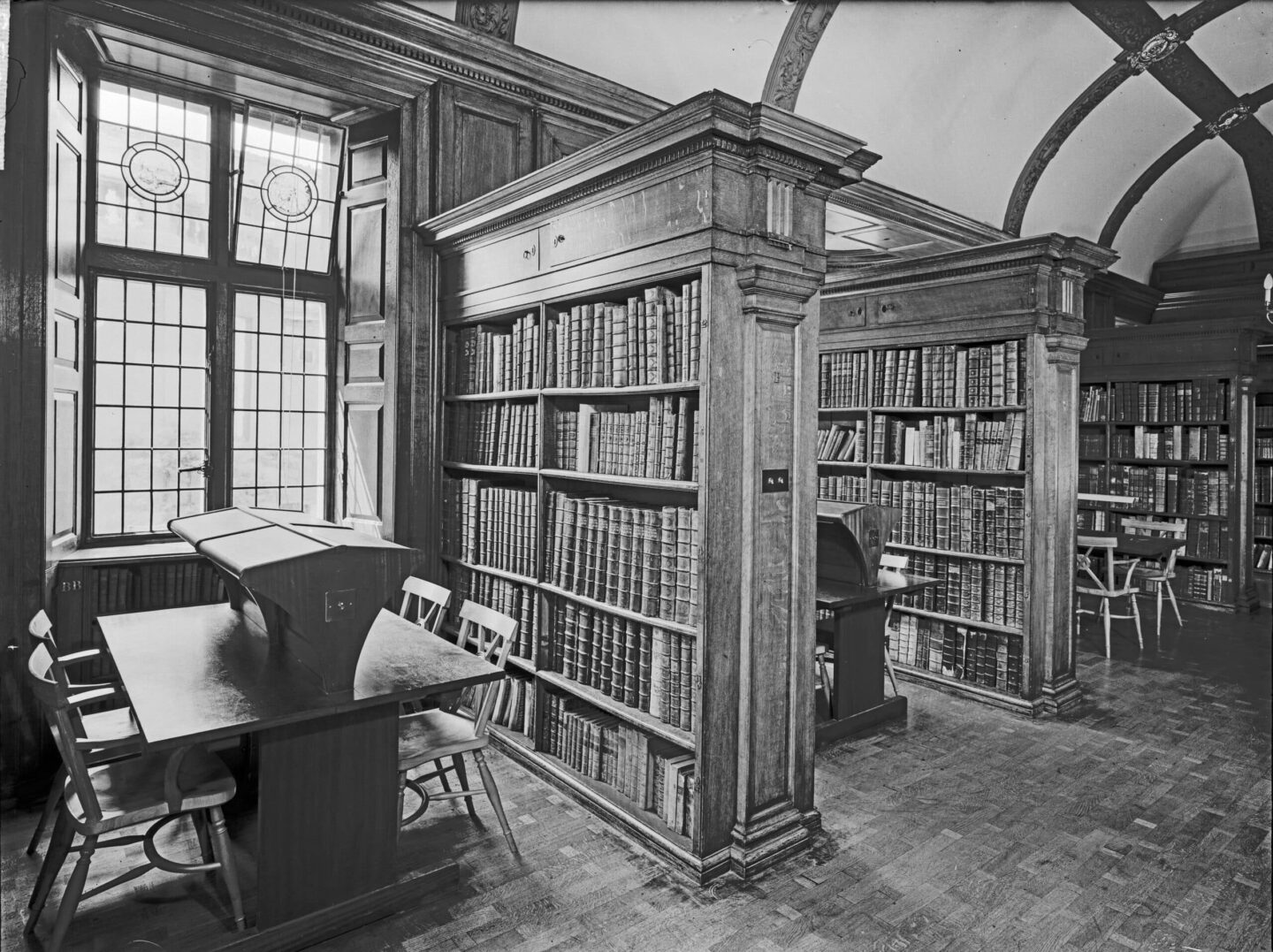

New shelves for the 18th century library

When the German scholar and bibliophile Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach visited Oxford to examine manuscripts in College libraries he found Lincoln’s library to be “cramped and very disorderly”. Perhaps in reponse to this criticism, the library was refitted in 1739 using a £500 gift from Sir Nathaniel Lloyd. For reasons that are unclear, Lloyd was less than pleased with how his money was used and swore to give the College nothing more! The shelves, which are still home to the College’s collection of early printed books, were fitted with a new system of rods and chains, making Lincoln the last of the Oxford colleges to retain the medieval practice of a chained library.

senior library

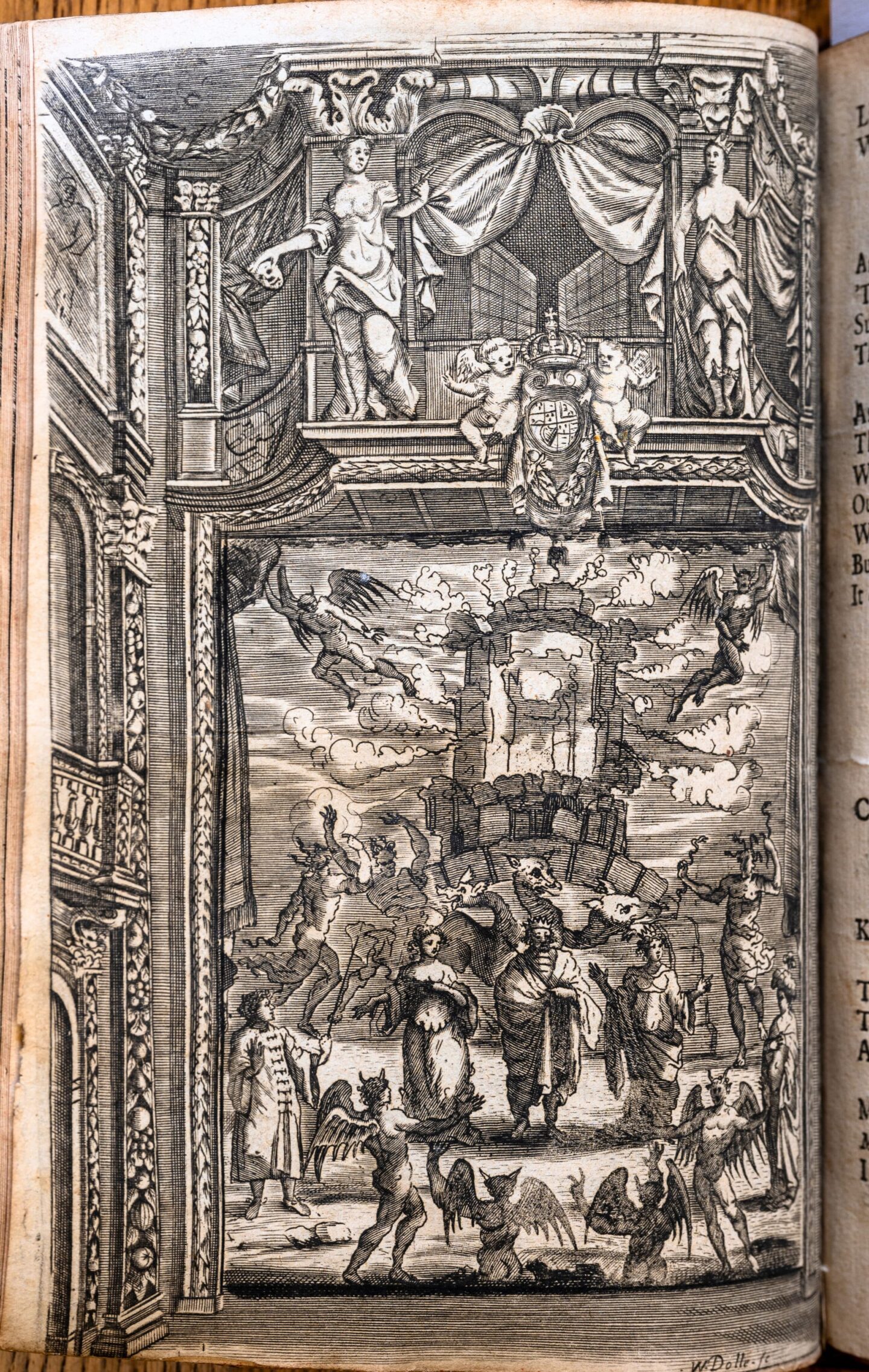

A Lincoln Fellow visits Drury Lane

Lincoln Fellow William Vesey, who died in 1755, was a long-serving member of College who served variously as Proctor, Sub-Rector, Archivist and de facto Librarian for over 50 years. The library he left to Lincoln has been described as “wide and civilised” but it also contains something rare in Oxford college collections: over 500 English plays from the 17th and 18th centuries. Vesey left no record of how often he visited the theatre, but the collection (which includes this edition of Elkanah Settle’s The empress of Morocco illustrated with stage sets from the period) suggest he was at least keen reader of plays.

senior library

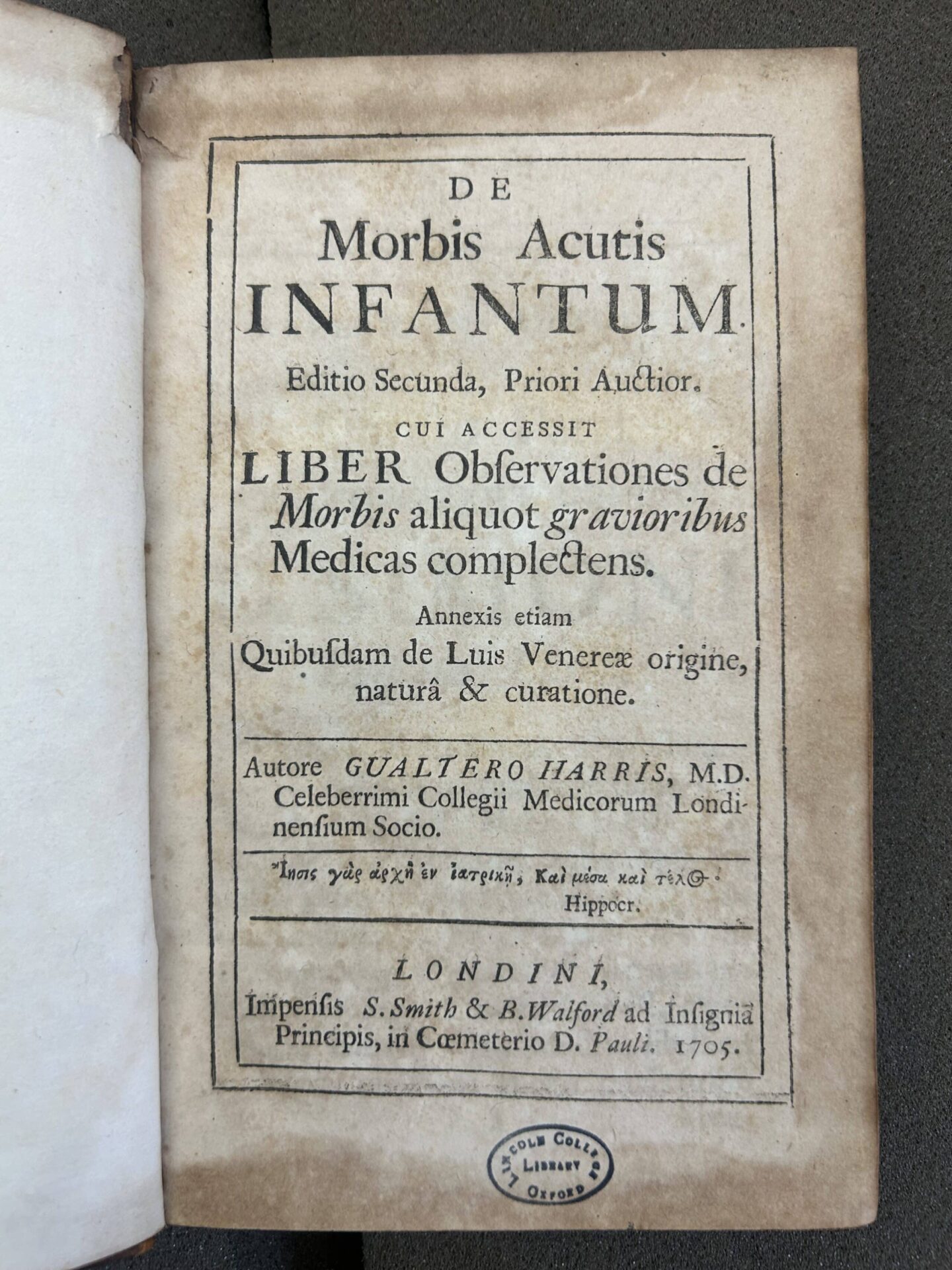

Studying medicine in the 18th century

Nathaniel Crynes was an English antiquary and physician, and an avid book collector whose library suggests he was a man of wide-ranging intellectual and scholarly interests. In his will, Crynes (who died in 1745) stipulated that the Bodleian should take those of his books it did not already own and that the rest should go to three colleges: Lincoln, Balliol and St John’s. The books that came to Lincoln included not only important editions of classical works but medical and scientific texts that, like Walter Harris’ work on childhood diseases, were fundamental to new areas of study.

senior library

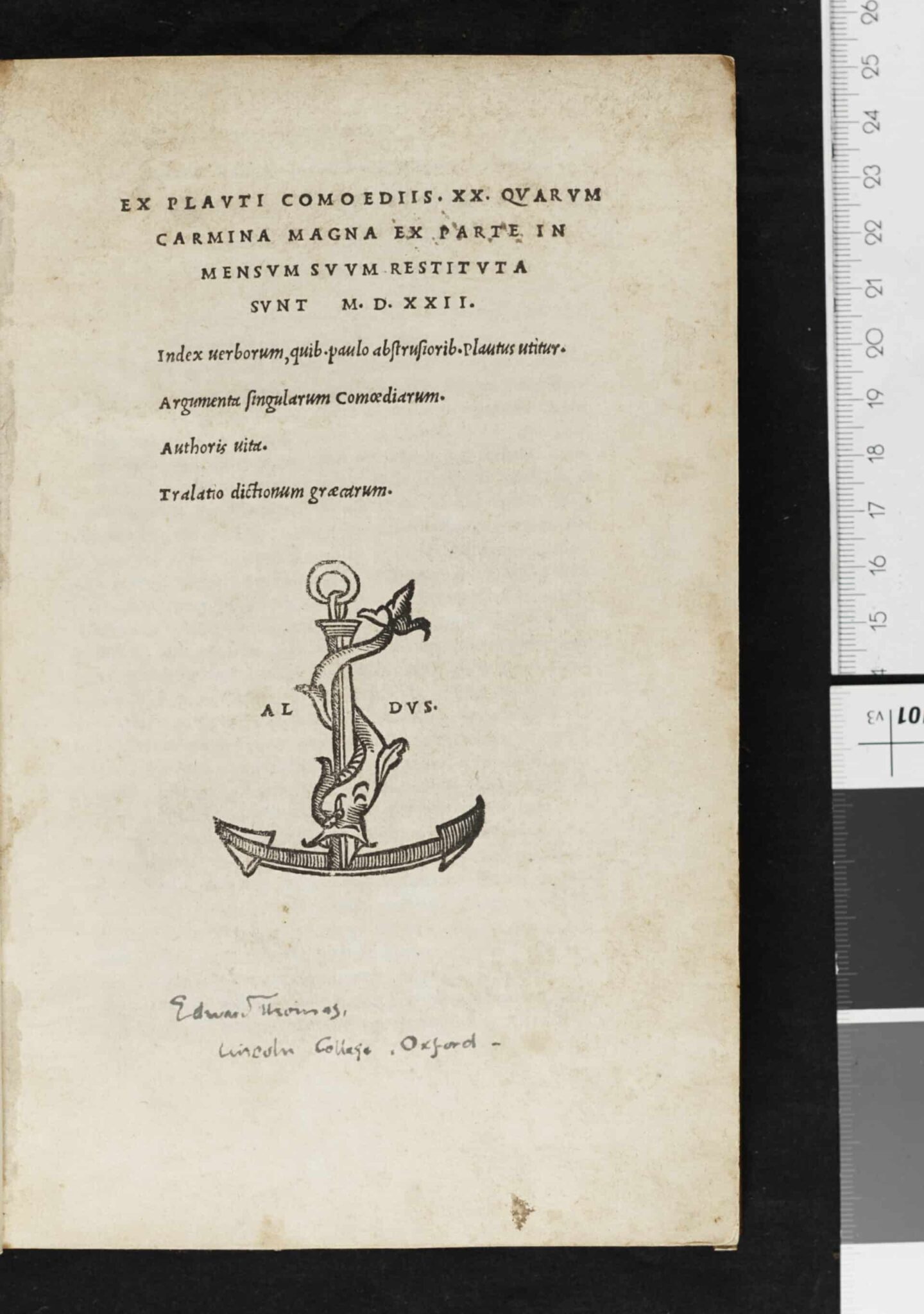

Edward Thomas at Lincoln

The poet Edward Thomas was an undergraduate at Lincoln, graduating in 1900 with a degree in Modern History. In 1968 and 1969 Myfanwy Thomas, his daughter, gave the College a collection of papers relating to Thomas’ life and work: these include an autography copy of his poem Roads (written on the back of a letter to his wife), and his annotated copy of Shelley’s Poems. The Senior Library contains Thomas item, given by him in 1903: a 1521 edition of the works of Plautus, printed in Venice by Aldus Manutius. While the book contains no evidence of Thomas’ reading of Plautus, it does contain manuscript notes in a 16th century hand: a rare example of the work of scholars employed by printing houses in the period to annotate texts before they were sold.

senior library

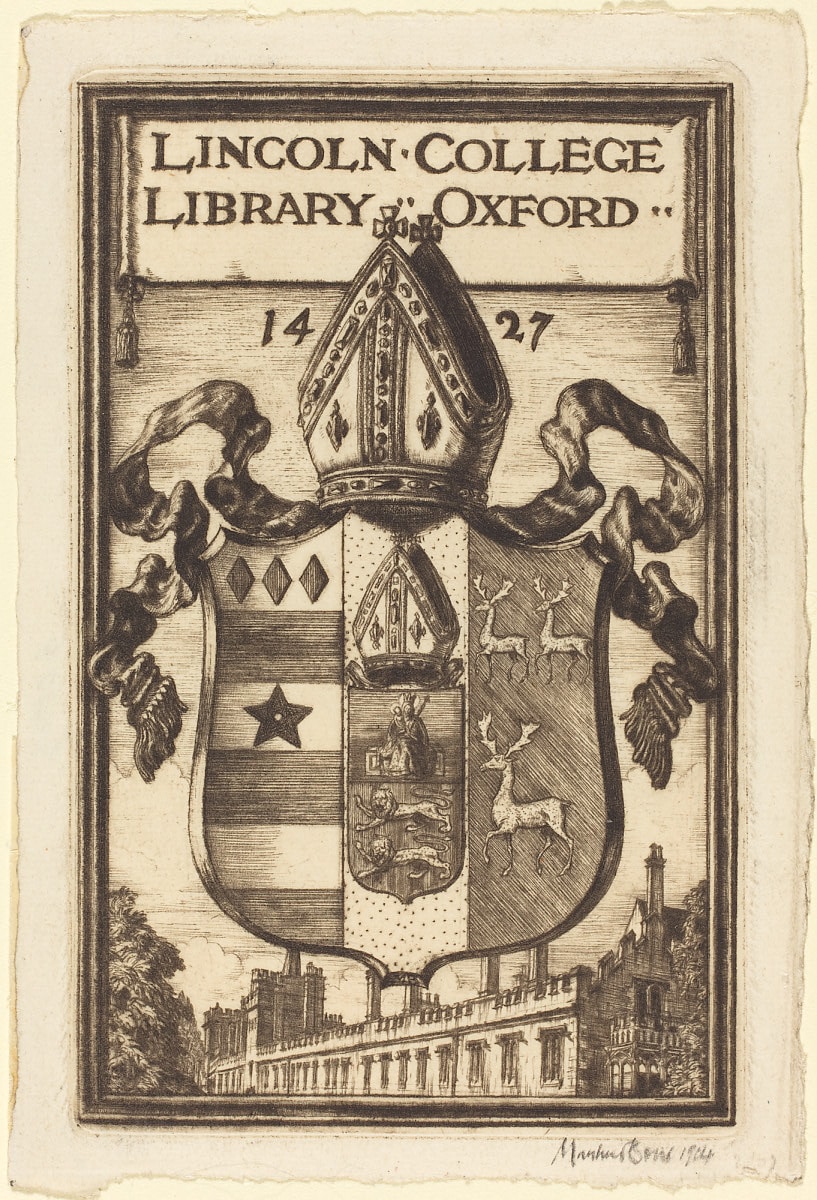

A new bookplate

With plans afoot to move the library from what is now the Senior Common Room to a new building at the end of the Fellows’ Garden, in 1904 a new bookplate was commissioned from the Scottish artist David Muirhead Bone (1876-1953). Muirhead Bone later became known for his work as a war artist and for his depiction of industrial and architectural subjects. In this bookplate, the College arms sit on top of the buildings that line Turl Street. Impressions of the bookplate were presented by William Walter Merry, Lincoln’s Rector, to public collections in Berlin, Boston, Bremen, Dresden and London.

senior library

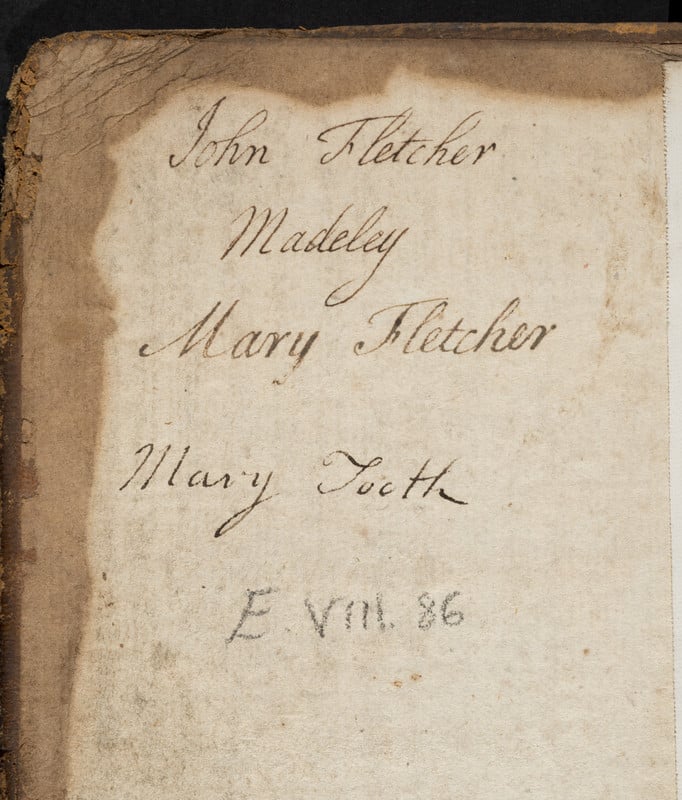

A 1952 donation to the Wesley Collection

It is no surprise that Lincoln’s Wesley Collection tells the story of the early years of Methodism in Oxford and Wesley’s years as a College Fellow. But the collection also tells us about Methodist communities with no connection to Oxford at all. In 1952 Mrs May Hall gave Lincoln the library of her husband, the Reverend Albert Hall. Many of these books – largely hymns and sermons – belonged to individuals and communities in the Yorkshire towns where Methodism flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries and are a valuable resource for learning more about these communities. Hall’s library also provides evidence, like this hymn book inscribed with the names of Mary Fletcher and Mary Root, of the important role women played in the early Methodist community.

senior library

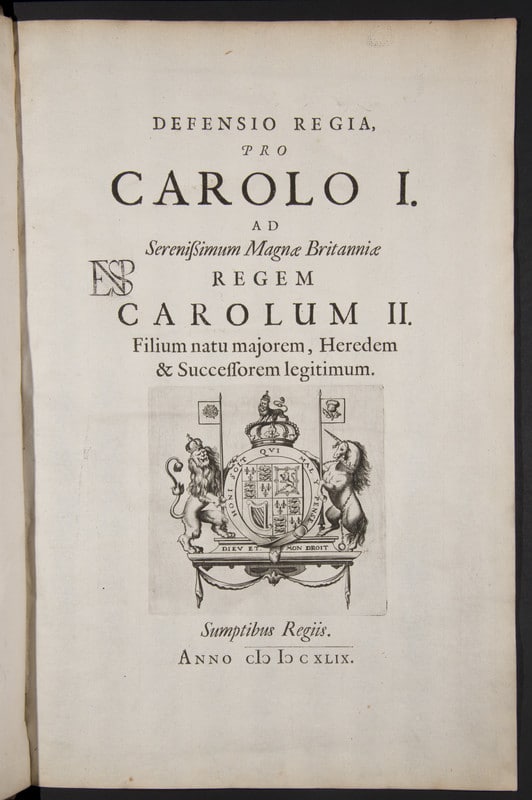

The library of a 17th century English statesman

A 1661 manuscript catalogue offered for sale in New York in 1956 offers a rare record of the working library of a 17th century politician: Sir Edward Nicholas (1593-1669), Secretary of State to both Charles I and Charles II. The catalogue was bought by Donald Nicholas - Lincoln alumnus and a descendant of Edward Nicholas. Using the catalogue as a guide, Donald Nicholas set out to reconstruct the library of his distinguished ancestor, evidently combing the catalogues of booksellers and auction houses for copies, including those with the ENSP inkstamp that – rather mysteriously – identifies Nicholas’ books. This valuable collection is now in the Senior Library.

senior library

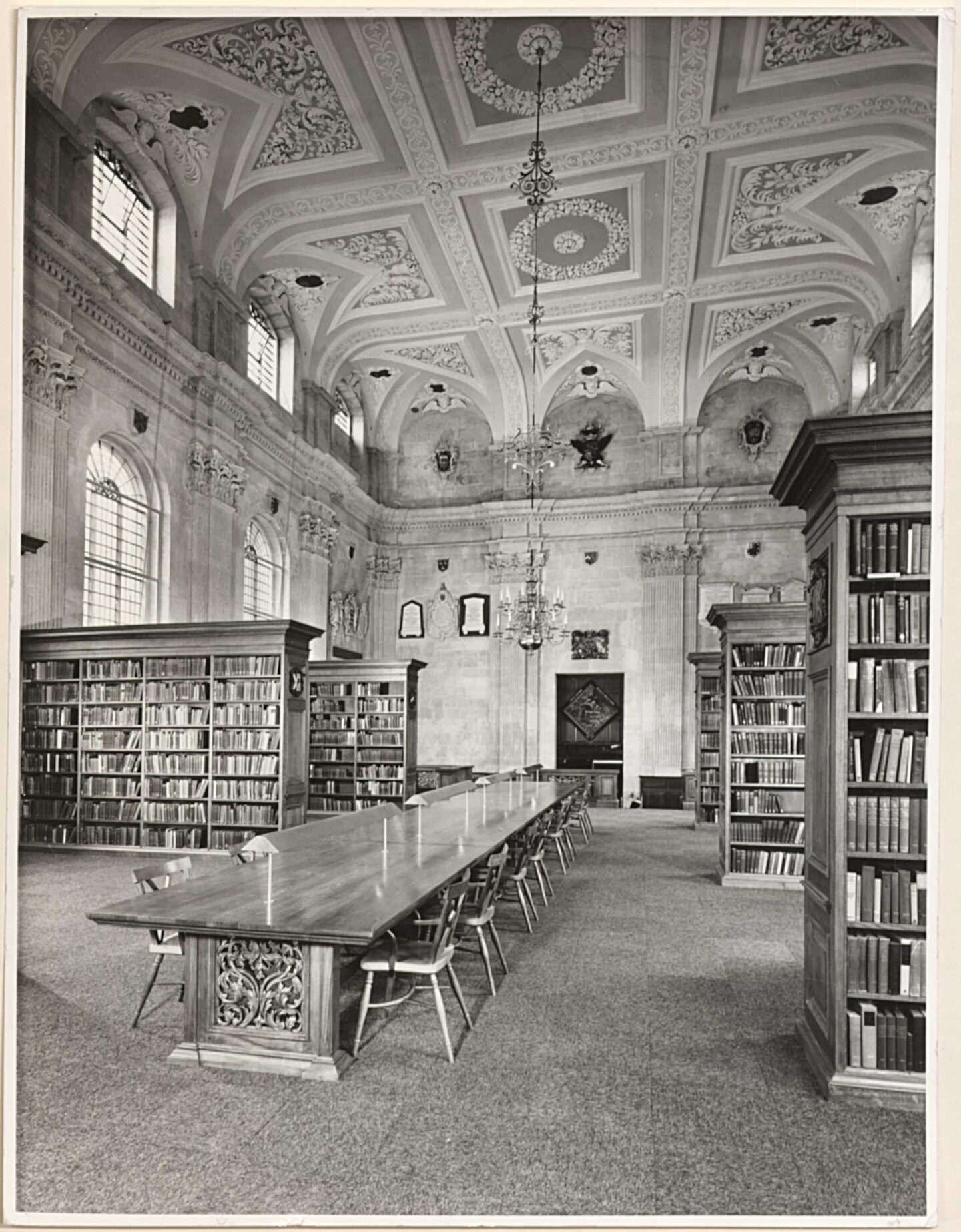

Creating a library in a church

All Saints Church became the College library in 1975: the conversion was the work of the architect Robert Potter (1909-2010) and cost about £420,000. The floor for the main part of the library was raised and space for a lower reading room was excavated. The Senior Library was moved into a room beneath the east end of the Church that was fitted out with 18th century panelling and the bookpresses made for the College in 1739 with money from Sir Nathaniel Lloyd. This room is now the Senior Library, home to the College’s collection of early printed books.

Archive

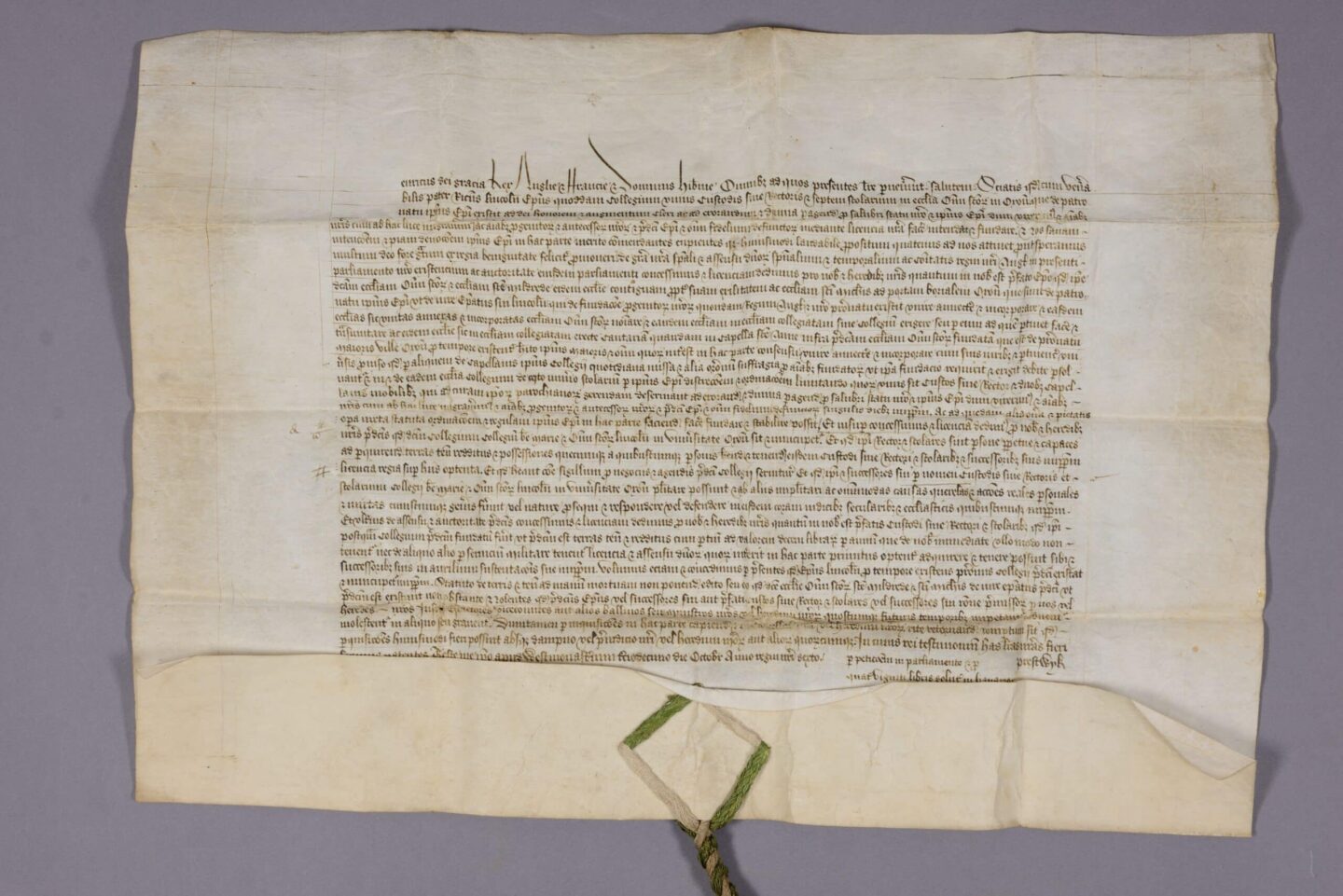

It begins with the Foundation Charter

Richard Fleming, Bishop of Lincoln, petitioned King Henry VI to found a ‘little college’ by incorporating the parishes of All Saints, St Michael’s at the Northgate, and St Mildred’s in the centre of Oxford. The latter church was knocked down to begin building the Front Quad.

Lincoln’s charter is interesting because it was written at the court of Westminster (visible on the bottom line) and sent up to Oxford, where the guidelines for decoration and gap for the decorative initial ‘H’ went un-illuminated, perhaps owing to the poverty of the early college. The Foundation Charter is the instrument by which Lincoln College is functioning today.

Archive

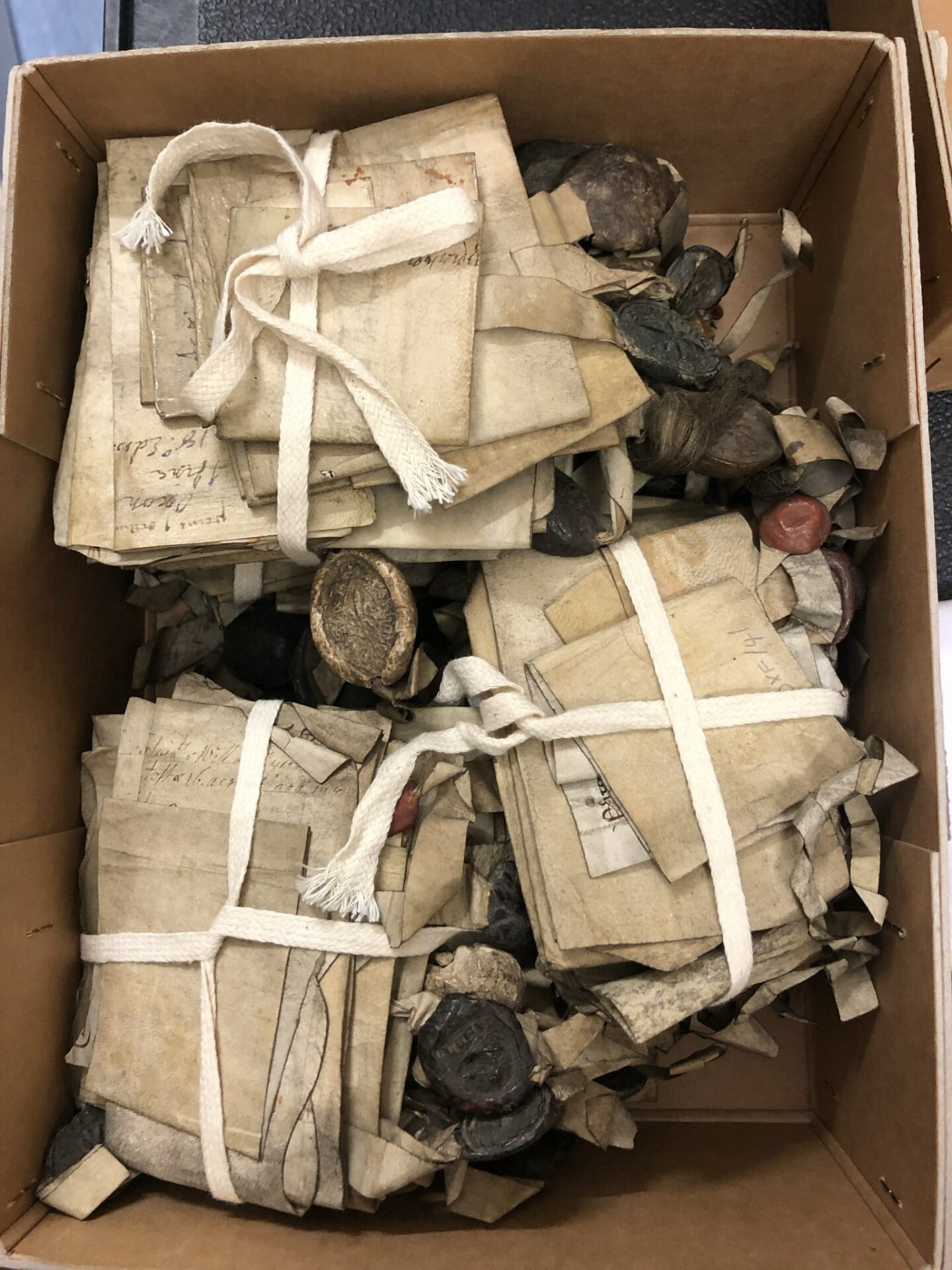

Doing Business: College Seals

These were essential for transacting business in the 15th century. The smaller wooden-handled seal features St Hugh of Lincoln and a legend “Sigillum Collegii Lyncolne in Oxonia ad causas”. There is still red wax visible around the edge of the silver matrix. The circular silver seal is the larger common seal, and intended for use in a press. The iconography features St Hugh of Lincoln and possibly St Richard, for the College founder Richard Fleming, Bishop of Lincoln. It has its own bespoke wood, metal and ivory box.

Today’s College seal is the same design as the common seal, but applied crimped on a red wafer.

Archive

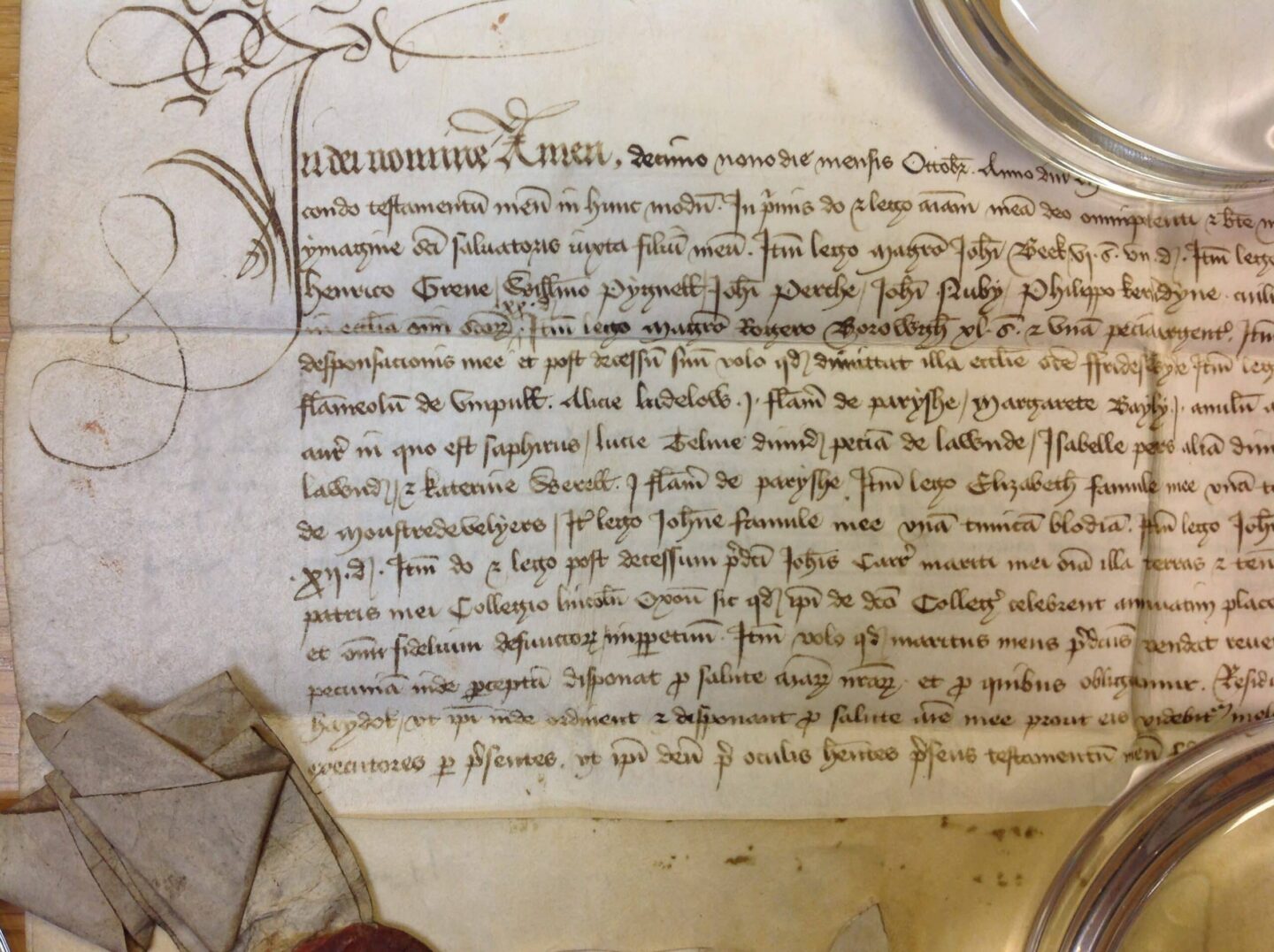

Earliest Female Benefactor: Emily Carr’s Will

Emmelina (Emily) Carr was one of the earliest benefactors of Lincoln and one of only a few female benefactors before the 20th century. In her will, dated 19th October 1436, she left instructions that she should be buried in All Saints Church (now the College library) and that the property she had inherited from her father should pass to the College on her husband’s death. Lincoln alumni might recognise her name: the Emily Carr party, themed and in fancy dress, is still an important event in the College calendar.

Archive

Royal Pardon

The monumental Great Seal of Richard III, the last of the Plantagenet kings, appears on a charter that was issued just a few months before he was killed on a battlefield in Bosworth in 1485. The charter gives a royal pardon to Rector George Strangeways and Lincoln’s Fellows for all the transgressions they had committed before Richard ascended to the throne in 1483. This allowed the College to continue to exist under the new monarch: if the charter had not been obtained, the College would have had no royal sanction and would have ceased to operate. Though there are 22 Great Seals of the monarchy in Lincoln’s archives, this is the only one from the controversial Plantagenet king.

Archive

Medium Registrum, Coat of Arms

When the magnificently-titled Portcullis Pursuivant of the College of Arms made a visitation to Oxford University in 1574, he ratified, confirmed and recorded Lincoln's coat of arms. The College arms, then as now, incorporate three different coats of arms: those of the See of Lincoln, in the middle, flanked by the arms of College Founder Richard Fleming, on the left , and of Thomas Rotheram, who re-endowed the College in 1478, on the right. The original rendering of the crest was attached to the inside front cover of the Medium Registrum for safekeeping, where it remains still.

Archive

Wood & Metal Strongbox

This small cashbox dates from the 1500s and is made from oak planks covered with black cuir bouilli and iron strapwork with iron fixings. The ironwork on the lid of the box is decorative while the underside of the box shows the well-preserved red leather straps.

Though it may have been used exclusively on Turl Street, one likes to image intrepid Bursars and Fellows down the centuries collecting rents during the College ‘Progress’ with the tenants of the estates. The mechanism would allow the lid to be locked shut, and then the box to be fixed to a wall or within a safe. This could keep these vital funds secure while travelling

Archive

I predict a riot!

Some of the most important documents in the archive are the court records of the manorial courts outside Oxford which the Rector, as Lord of the Manor, could convene for those who lived on College estates.

Chalgrove, Oxfordshire was one such estate. At the Easter session of the 1678 Quarter Sessions, charges were heard arising out of a riotous dispute over the ownership of 9 acres of land in the manor of St. Cleres. The College’s tenant was Elizabeth Wiggin, a widow; the counter-claimants were Frances Quatermain and his family.

Both sides were indicted for riotous assembly and assault & battery. Lincoln College instructed Mrs. Wiggin to cut and carry away corn growing on the land and paid Robert Quatermain £50 to renounce all future claims.

Archive

Building a College Chapel

It is maddening for scholars of our ecclesiastical and architectural history that the accounts of the years when the current Chapel was built (1629-1631) are missing from the otherwise-extensive series of college records. In his research into the building of the Chapel, Dr Mark Kirby (Lincoln) has had to piece together evidence from other sources within the archive and further afield.

One theory about the missing accounts is that the College Visitor, Bishop of Lincoln John Williams, ordered the accounts to Westminster Abbey where there was a fire in the Chapter Library in 1694. Williams may also have paid for the chapel out of his own household, whose accounts for the period are also no longer extant. What remains is the magnificent Chapel which has welcomed members and visitors for nearly 400 years.

Archive

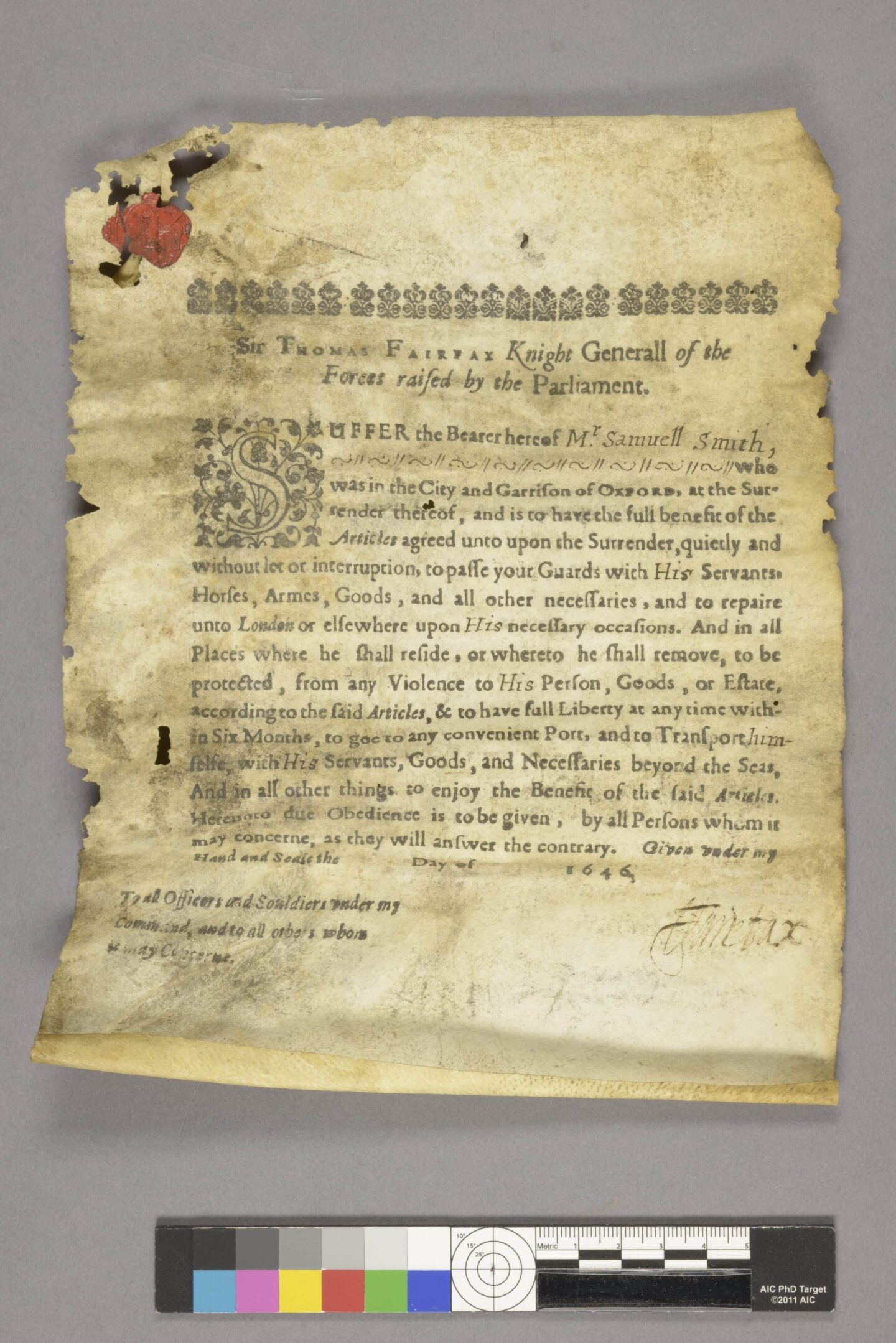

A Civil War Passport

Charles I established his headquarters in Oxford during the English Civil War, and had to house his court and administration across the colleges and town. We know from sources in the archive as well as in the Bodleian that the room which is now the upper Senior Common Room was used as the Exchequer of Receipt during the War.

The College Visitor, the Bishop of Lincoln, Robert Sanderson, was writing to college during that time. His letters regarding the Civil War also remain in the archive (LC/C/COR/8/1). In common with other colleges, Lincoln surrendered its silver to be minted into currency at Oxford’s mint. The only surviving pre-Civil War silver at Lincoln is the Chapel candlesticks given by

The most remarkable survival was found up a disused chimney during recent renovations at the Ede & Ravenscroft store, in a property owned by Lincoln. It is an early proforma passport made out to Mr Samuel Smith, signed in 1646 by signed by Sir Thomas Fairfax, 'Generall of the Forces raised by the Parliament'.

Archive

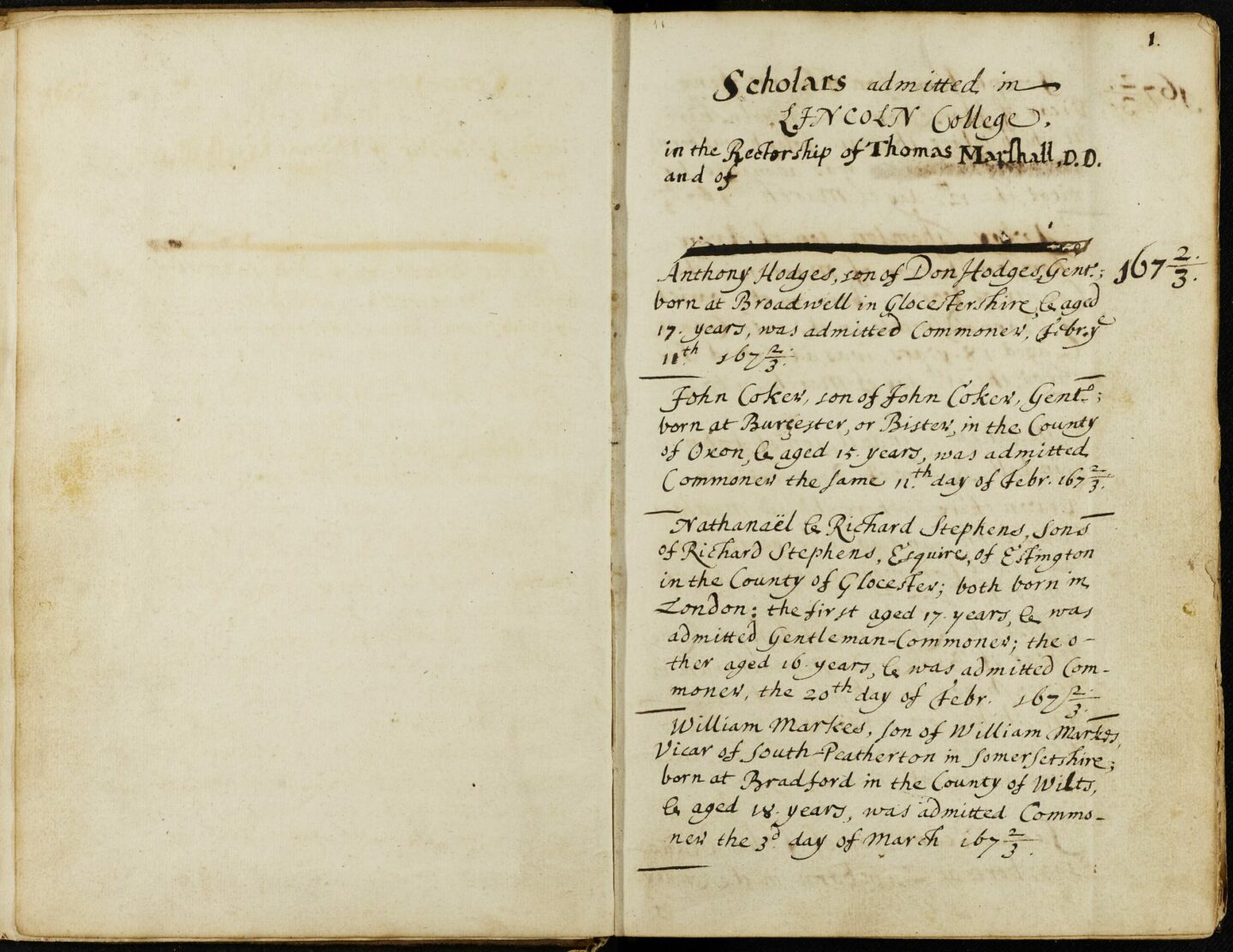

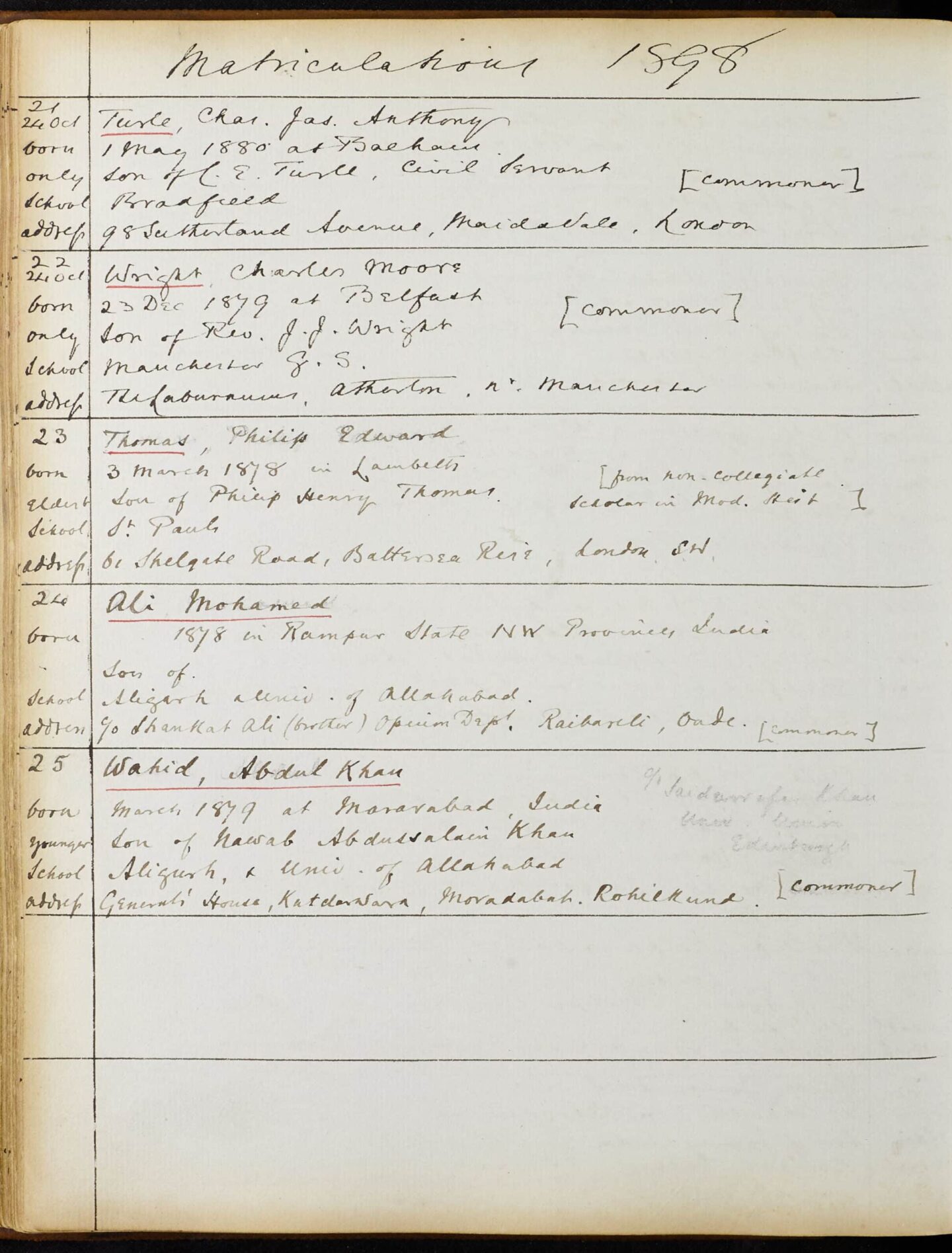

Who’s Who

Lincoln must have kept records about its students from its foundation in 1427, but the first surviving student register dates from 1673. Headed ‘Scholars admitted in Lincoln College in the Rectorship of Thomas Marshall’, the 1673 matriculation register records a student’s name, age, where he was born and the date of matriculation. It also records the name and rank of his father. Students are grouped into categories of undergraduate: commoners, scholars or exhibitioners, gentleman-commoners, servitors, or the Bible Clerk. The first three categories still exist, but the latter three ceased in the 19th century.

Fully digitised and indexed, these registers are the vital starting point to numerous avenues of research.

Archive

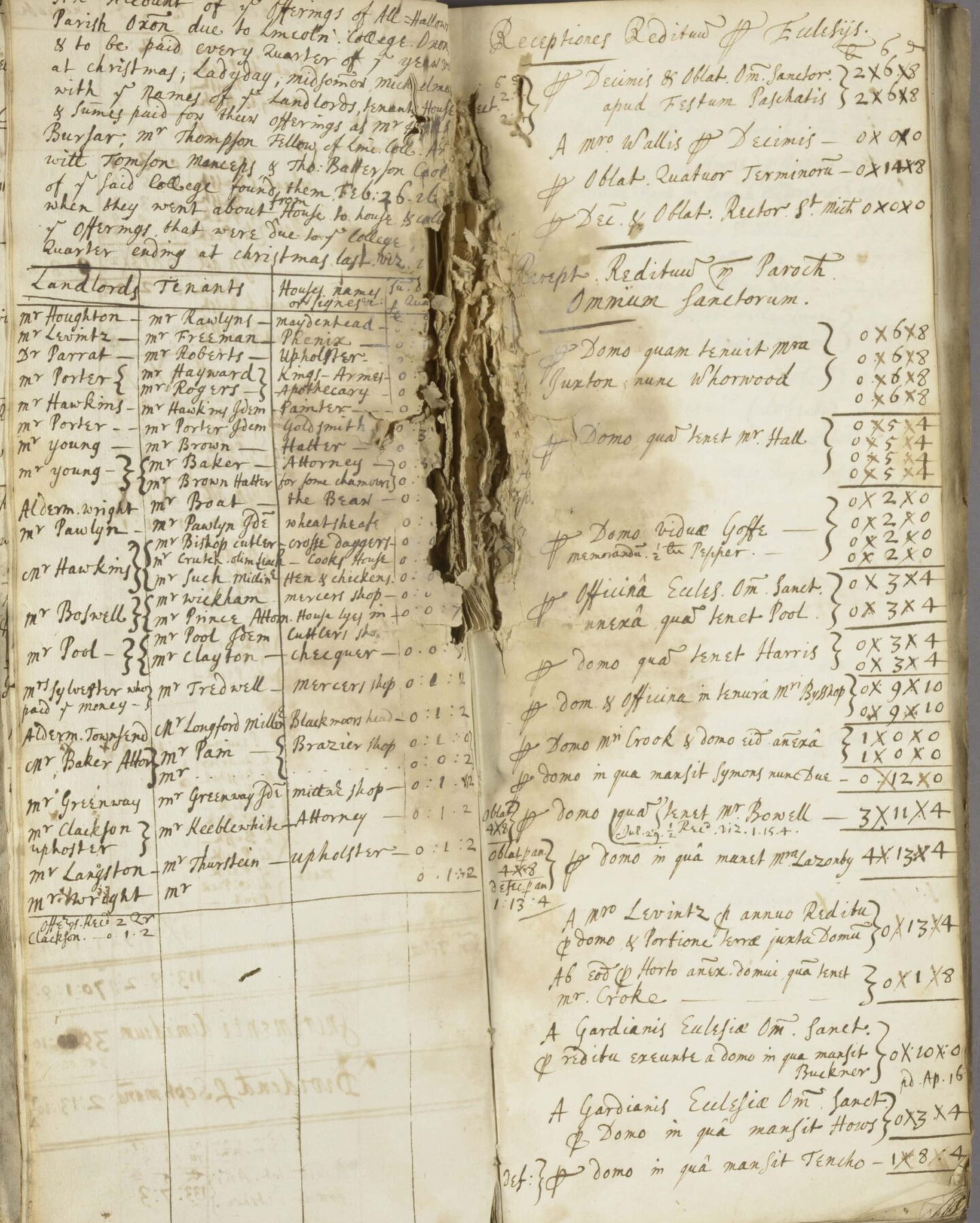

Vesey’s Day Books

Lincoln Fellow William Vesey (d.1755) was on frequent rotation as Bursar when this position was an annual election from amongst the fellowship. He evidently had a knack for keeping control of the college finances, or at least ensuring that they were well recorded. He went back to previous ‘day books’ (the rough-running accounting volumes used to prepare the fair annual account) and annotated them with additional information; he also used them to record inventories of items in college, such as cutlery, silver, napkins, and other necessities held for the common table.

Vesey’s day books are a treasure trove of information about the daily life of Lincoln in the 18th century. Unfortunately, he seems to have kept them against a damp wall in his rooms (now the Wesley Room), as all have a similar pattern of damage from the moisture. The day books have now undergone conservation and are fully digitised.

Archive

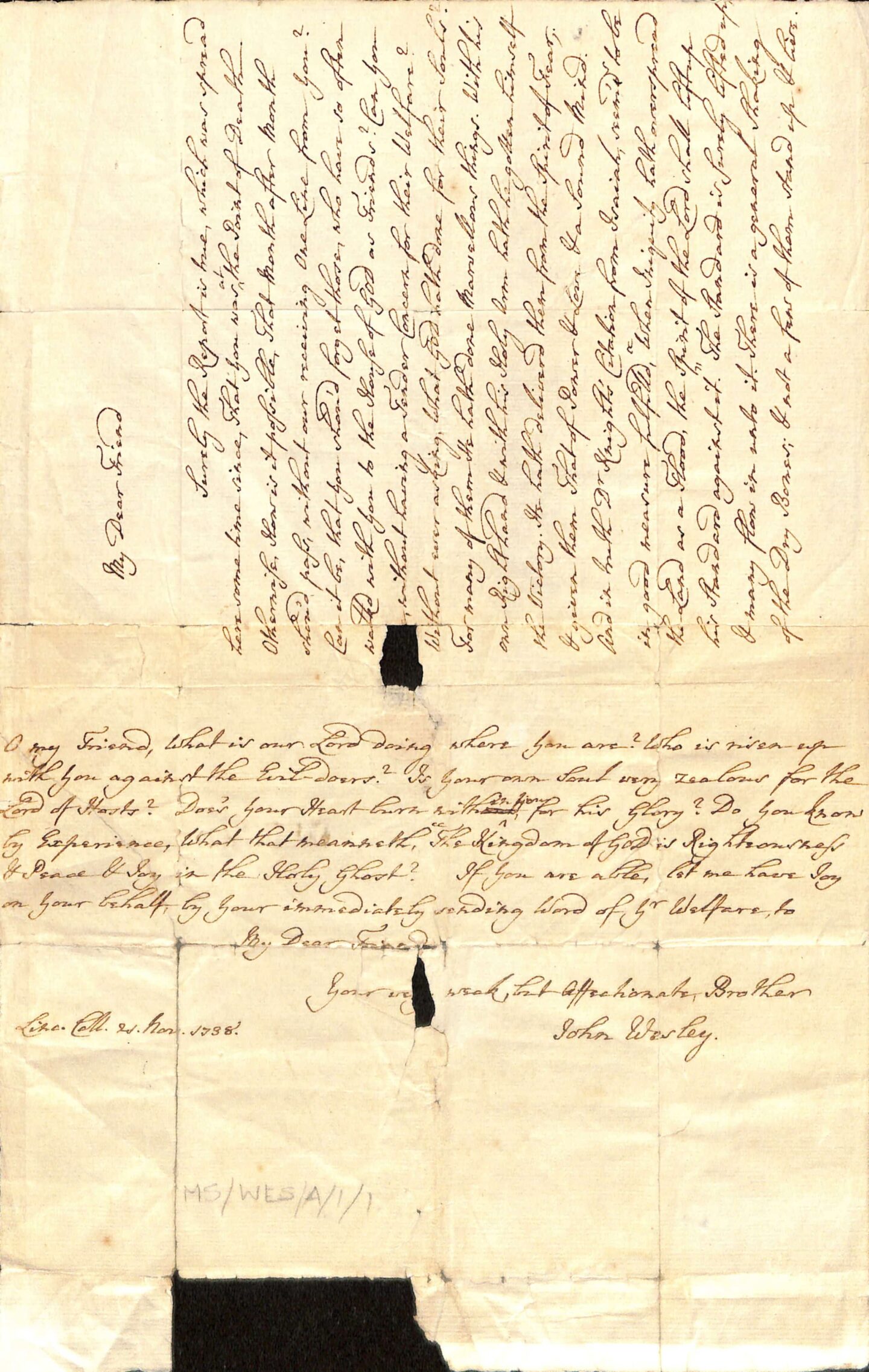

The young John Wesley

John Wesley was elected Fellow of Lincoln College in 1726, only resigning when he got married in 1751 (in this period, fellows were required to be single men in holy orders). Old Members have generously donated letters, publications and objects owned by or related to John Wesley and early Methodism over the three centuries since his election.

One letter in the small Wesley collection in the Lincoln archive is to his former student James Hervey. Beginning "My Dear Friend", Wesley gently chastises Hervey for not returning his letters. He enquires about Hervey's spiritual life, and that of those in Hervey's Devon parish. Though few in number in Lincoln’s collections, Wesley’s writings give plenty of insight into his character and religious views. These have been digitised so they can be studied from anywhere in the world.

Archive

Priest, Scholar, Politician, Benefactor, Boy-Racer

Nathaniel, Lord Crewe began his life-long association with Lincoln College when he matriculated as an undergraduate in 1653: he was elected Fellow in 1656, served as Sub-Rector twice and was elected the 18th Rector in 1668.

Crewe was a generous benefactor, sponsoring College fellowships and, in his will, setting up a charity (the Lord Crewe’s Charity) that still funds educational projects in Lincoln and elsewhere. He is also remembered for a rather flamboyant style, racing around Durham in his coach and team of eight horses.

Archive

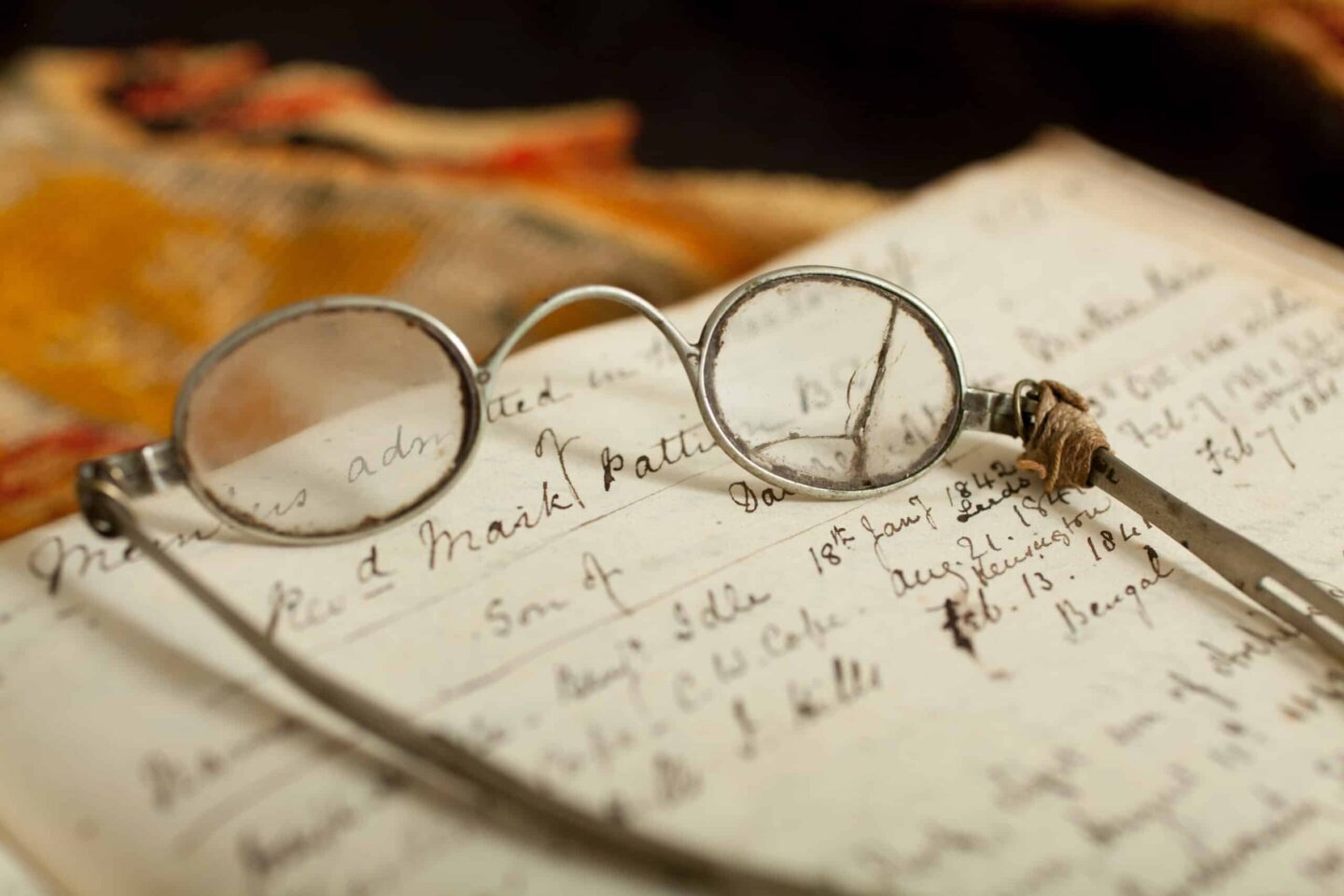

Pattison’s Specs

Classical scholar Mark Pattison was elected the Yorkshire Fellow in 1839 and, in a controversial Rectorial election (which inspired C P Snow’s The Masters), he became Lincoln’s 29th Head of House in 1861. Outspoken, critical and considered a difficult personality, Pattison continued to dominate and divide society within College and more widely across the University. Pattison’s work on the classical scholar Isaac Casaubon has stood the test of time, although he is perhaps better known now as the likely model for the character Edward Casaubon, the pedantic scholar and clergyman of George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

Records in the archive show Pattison aging as he presides over College business, with his signature becoming increasingly shaky and spidery. These spectacles, cracked and repaired, show us a more familiar and personal side of this formidable figure from Lincoln’s past

Archive

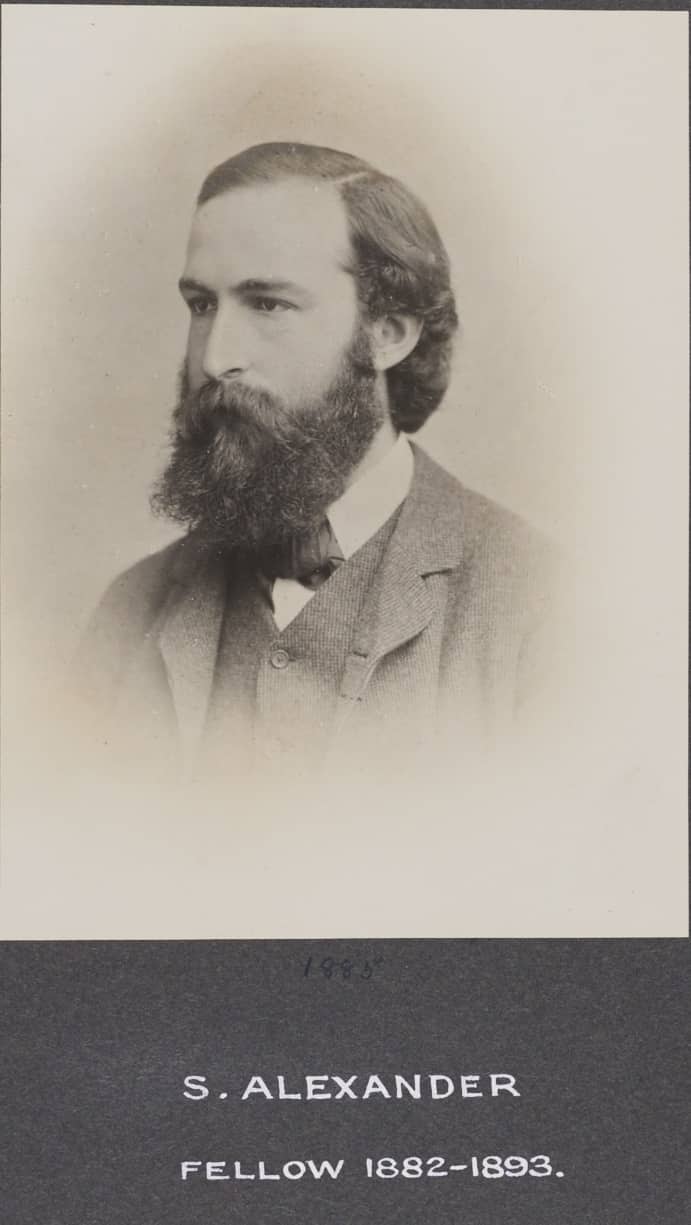

Fellowship election entry of Samuel Alexander

After University reforms of 1871 allowed non-Anglicans to become Fellows, the philosopher Samuel Alexander became the first Jewish fellow of any Oxford college when he was elected at Lincoln in 1883. Alexander’s arrival marked not only a new era of religious diversity in College, but also an intellectual one. His scientific approach to philosophy and experimental psychology, laid out in his 1920 work Space, Time and Deity, would have set him apart from other philosophers in Oxford.

Born in Sydney in 1859, Alexander came to Oxford after university at Melbourne on a scholarship to Balliol. He later moved on to Manchester, where he spent the rest of his career. However, he retained his affection for and affiliation with Lincoln College through his life, becoming an Honorary Fellow in 1918 until his death in 1938.

Archive

Matriculation register showing arrival of students from India

This page from the 1898 matriculation register shows the arrival at Lincoln of two students from India: Abdul Kahn Wahid and Mohamed Ali. Around 1892, University regulations allowed students with a first degree from universities on the Indian sub-continent to matriculate in Oxford; Ali and Wahid both took degrees from the University of Allahabad before coming to Lincoln. Evidence from the archive shows that up until 1918 the largest number of Lincoln students born outside the UK have come from the Indian sub-continent. Many came to prepare for the Indian Civil Service examinations administered in London.

Archive

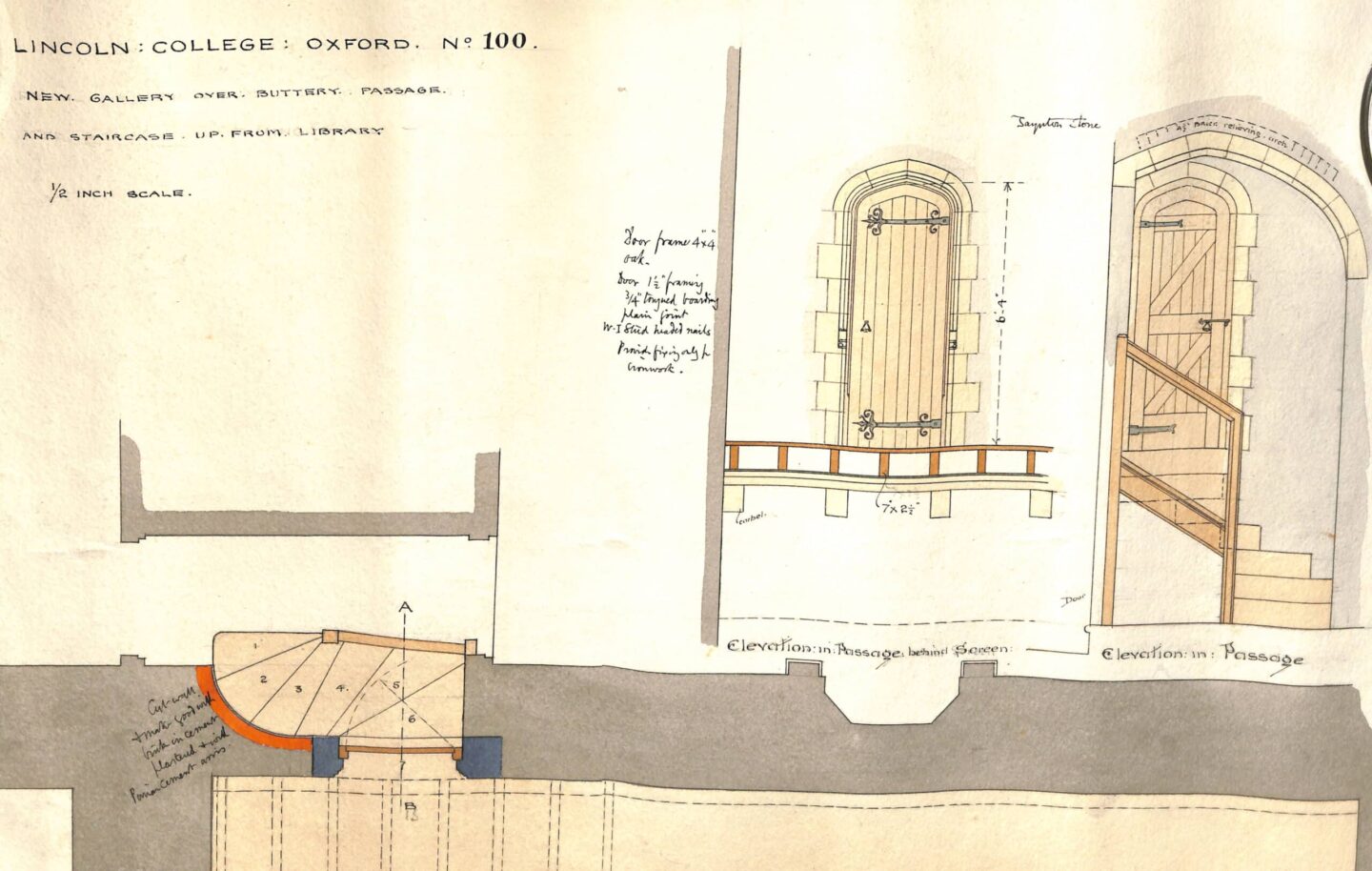

Evolution of the heart of the College

The dining hall was constructed around 1437 along the east side of Front Quad through the generous benefaction of Dean John Forest. It was an early place of socialisation for College members with a floor of trodden earth. Wooden boards and a paved hearth were laid about 1507. The windows were glazed and there was some form of wall-hangings. Furnishings included: a pewter sink and ewer for hand-washing, simple tables and benches, a chair for the Rector, and a desk for the bible clerk to read from the Bible. A door with direct access to the Rector's original lodgings was added in 1528. In 1891, the eighteenth-century plaster ceiling was removed, exposing the original roof beams, and the windows were removed and replaced with faux-Gothic reconstructions. A new ornate fireplace was also added to the design of T G Jackson. Access to the gallery and repurposing that space as part of the Library was proposed, but never executed.

Archive

Rowing for Lincoln

The Lincoln College Boat Club has kept excellent records, for example a series of five boat club photograph albums covering the years 1882-1974. Each page is filled with a photograph of a team, with the names of individual rowers and their place in the boat written alongside. Sometimes even their weight is noted!

The Boat Club also kept written records, including minute books, club rules, information about race dinners, and accounts. The accounts are particularly interesting: one entry show extra money for a ‘training diet’ that seems to have consisted entirely of milk!

Archive

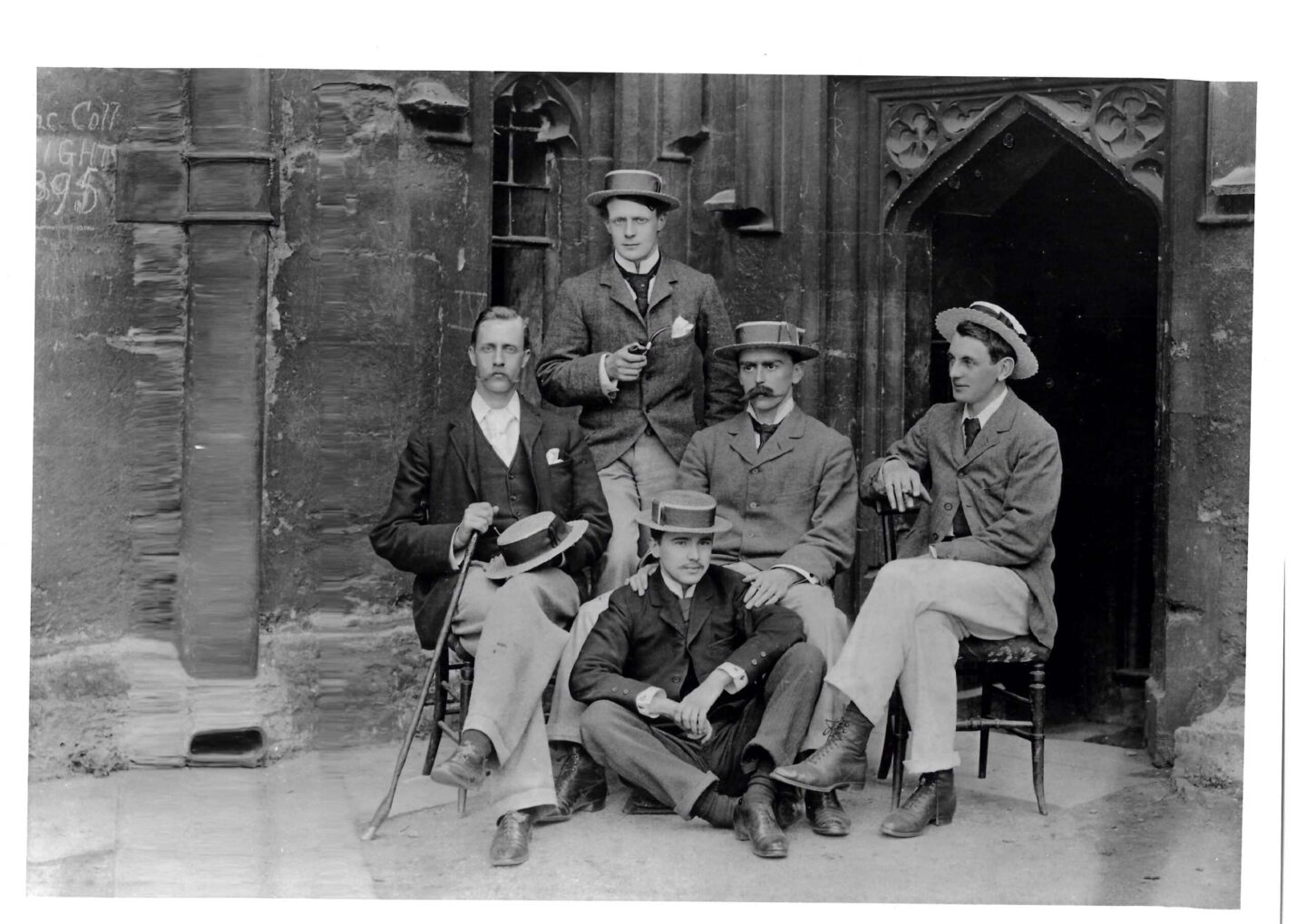

Fragile artistry: history on glass

Lincoln alumnus Arnold Fairbairns (1881-1918) was a gifted photographer. His evocative images of Lincoln College and College estates outside of Oxford (one pictured here) were used by his friend Stephen Warner in his 1908 College history. Fairbairns’ images give an unrivalled sense of the College in this period: its buildings, estates, documents and, perhaps most importantly, its community. His glass plates negatives, which have now been digitised, bring the early 20th century College to life.

Archive

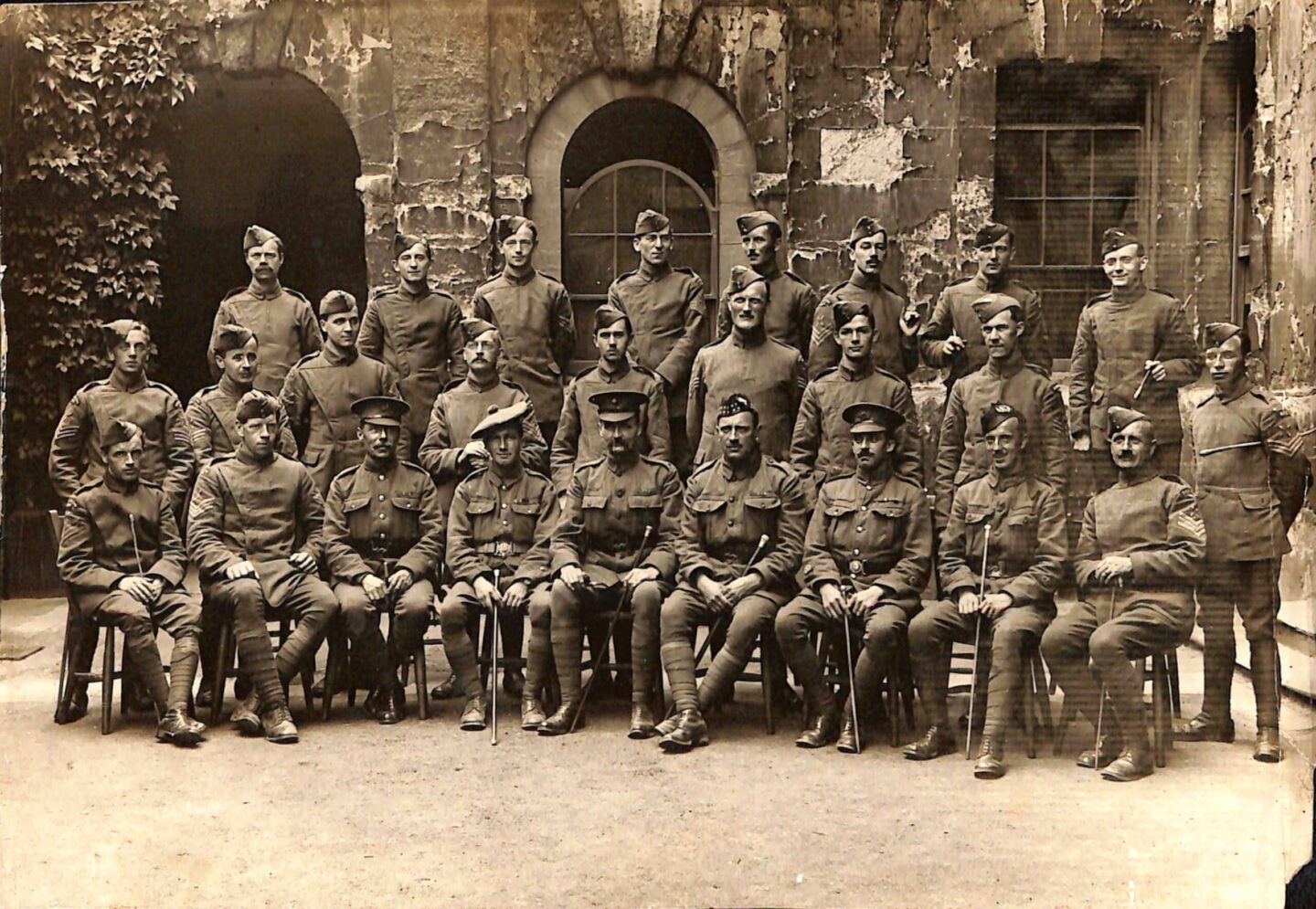

Lincoln in WWI

Wartime changes everything and Lincoln was no exception. During WWI most of the College was given over for the use of the officers training in the Royal Flying Corps, the predecessor of the RAF. The men lived and dined in College while training at the airfield at Port Meadow. This change of use perturbed a few of the older fellows who were still in residence, being exempted from war work. They complained that the officers were soiling the antimacassars in the Senior Common Room with their hair cream.

More pressing for the nation was the need to enlist men of age. College servant Frederick R Harris was one such individual. Born in 1890, he serviced in the Royal Flying Corps for the duration of the war, leaving his wife Carrie in Oxford. A small cache of records and photographs was discovered by a family friend in Harris’s attic in 2017, and donated to Lincoln’s archive. There are photographs of Frederick with his regiment in Front Quad, and also with a group of college servants of various regiments. Harris obviously took pride in his work in the buttery, as one item he kept was a list of ‘Prominent People F R Harris has waited upon’. He retired on 29 September 1959, and died in 1985.

Archive

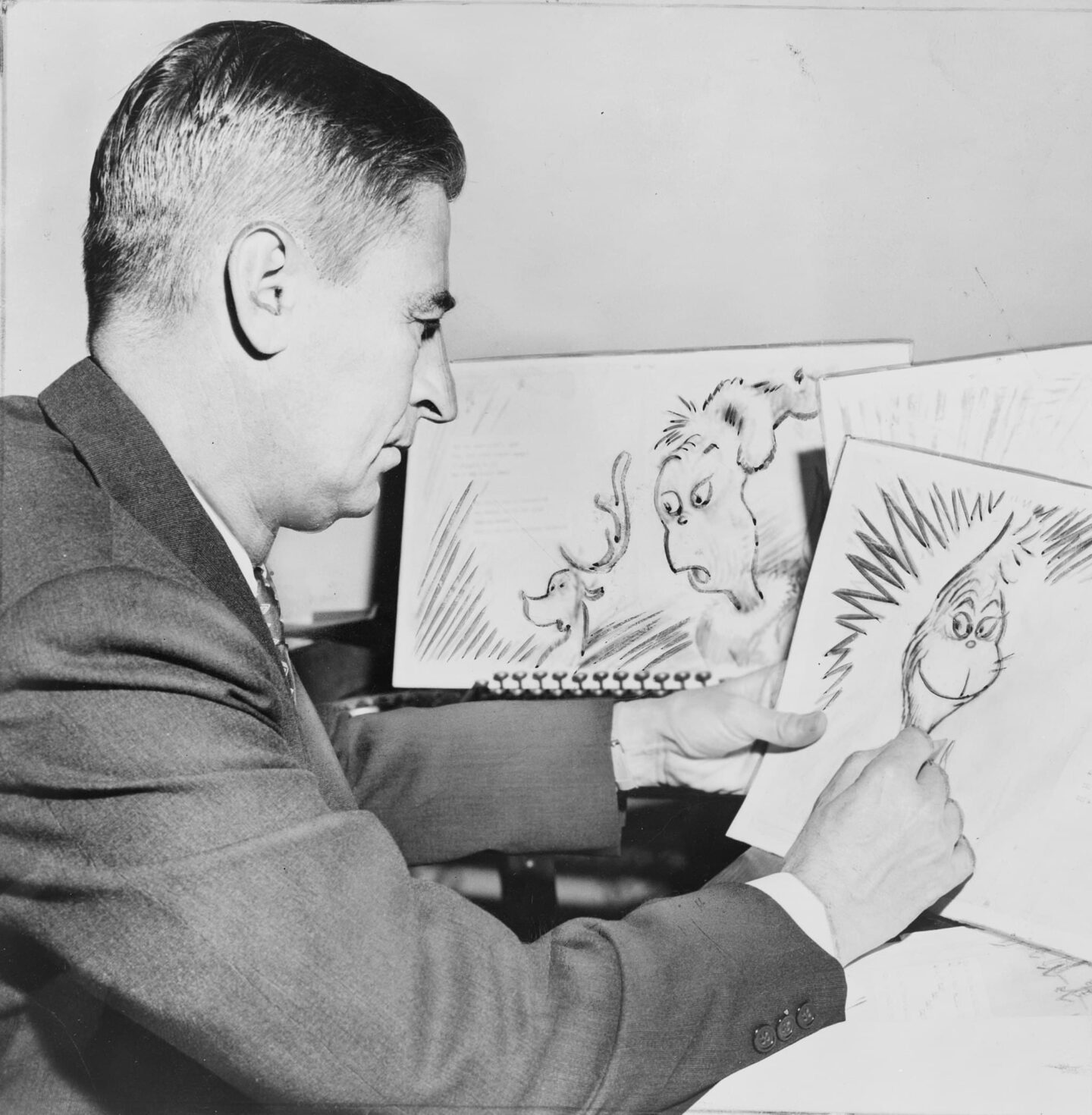

Lincoln Hears a Who!

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr Seuss, came to Lincoln College as a graduate student from Dartmouth College in 1925 to study English Literature. The 1925 Room Lists show that he was assigned to Staircase 6.9. His name is crossed out, indicating that he did not end up living there but took digs instead.

Though he had certainly left Lincoln for Paris a year later, his tie with Oxford would be life-long; here he met Helen Marion Parker, a teacher, whom he married in 1927. He did not complete his graduate studies, but instead styled himself ‘Dr’ for his nom de plume. His obituary in the Lincoln College Record 1990/1 states, “No Lincoln man has ever had a wider audience as a cartoonist, playwright and above all children’s author.”

Archive

Developing a Life-Saving Drug

One of the most significant medical advances of the 20th century took place at Lincoln when four College scientists helped to develop penicillin from Alexander Fleming’s initial work in the late 1920s. With WW2 raging, the stakes to develop a life-saving antibiotic could not be higher.

Howard Florey (pictured) and Ernest Chain began work on penicillin at the Dunn School in 1939, where they were able to purify it. Norman Heatley joined the team and was able to extract the drug to treat humans in 1941. However, he had to use an improved method involving bedpans, milk churns and baths to hand to try to treat the first patient.

Drug companies were able to then manufacture penicillin to scale enough to treat some of the military during some of the riskiest operations of the war.

Post-war, another Lincoln scientist, Edward Abraham, was able to continue work on antibiotics. He developed and patented cephalosporins. Their brilliant legacy has saved lives across the world.

Archive

“The Desire to Wander”: Denis Hill’s suitcase

Denis Cecil Hills (1913-2004) was a journalist, teacher and adventurer who, after serving as an officer in the British Army and the Allied Control Commission from 1950-1950, lived and worked in Germany, Turkey, Uganda, Zimbabwe (then Rhodesia) and Kenya. It was while he was teaching in Kampala that he attracted the attention of Idi Amin, being imprisoned and sentenced to death for sedition. He received an eleventh-hour reprieve when the then Foreign Secretary James Callaghan travelled to Uganda to release him from prison.

Hills prepared his archive before his death using a variety of cereal packet liners, plastic bags and repurposed envelopes. His battered suitcase (pictured) was bursting with his news clippings.

Archive

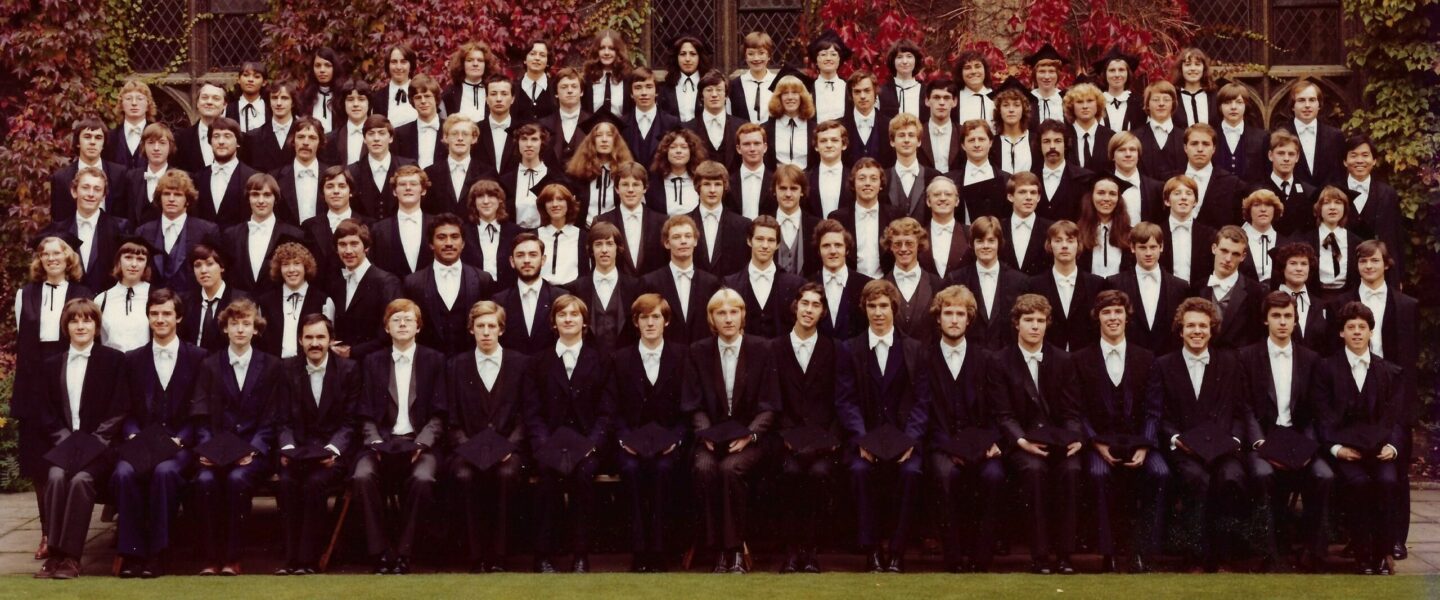

45 Years of Women at Lincoln

Lincoln was in the second wave of Oxford colleges to admit women in 1979 and greeted the new arrivals with flowers in their rooms. The womens’ names on the matriculation photograph are recorded with their title (Miss and occasionally Mrs) in case there needed to be additional differentiation from the men, recorded with their surnames. Along with an uplift in academic results, the following year also brought Lincoln’s first female Fellow: Dr Susan Brigden. An eminent historian, she tutored generations of Lincoln history students until her retirement in 2016. Her contribution of Lincoln is commemorated with her portrait in Hall.

Archive

Stephanie Cook with gold medal

Dr Stephanie Cook, MBE, became the first female athlete to win the gold medal in the modern pentathalon in the 2000 Sydney Olympics. She matriculated at Lincoln in 1994, following her studies at Cambridge, where she rowed and ran distance. She and pursued a career in medicine and combined arduous hours as a junior doctor while training before taking a short break to focus on Olympic preparations. Her work paid off when she finished three seconds ahead of the silver medalist at the Games.

She appeared on an episode of “This Is Your Life’, broadcast in 2002, and returned to Lincoln to open the new buildings at Museum Road in 2007. Dr Cook specialises in vascular surgery.

Archive

Ascension Day

The Christian Festival of Ascension has always held special significance in college. Having originally two , now one , collegiate parish adjacent, the beating of the bounds on this day is a way to continue ties with St Michael at the Northgate. The beating of the bounds concludes in College, followed by ivy beer in Hall or the Grove. This is an offering of hospitality to the parishioners and also to members of Brasenose, to whom the small door between the colleges is opened to invite them in.

After drinks are imbibed, the Lincoln choir sings from the gatehouse tower. Then pennies are thrown onto the lawn for the schoolchildren of Combe Primary School to collect. The prudent parents send baseball hats to provide some head and eye protection from the falling coins. In a small concession to health and safety, the pennies are no longer heated; this used to provide a salutary lesson about greed for the young visitors.

archive

The Imp

Half human, half animal, one leg crossed: the figure of the Imp has been used to represent the devil since the 13th century. An alto relievo of the Imp was installed in 1899 though the generosity of students JC Jack, HA Lomas, NB Page, and H Trask, likely replacing an earlier figure.

Stephen Warner’s 1908 college history calls the Imp Lincoln’s “overseer, adopted from the figure in the Angel Choir in Lincoln Cathedral”. Folklore says that two mischievous imps were dispatched to Earth. When they got to the city of Lincoln, one was struck by the cathedral’s beauty and turned to stone in the Angel Choir. The other ran to Oxford to Lincoln College.

The earlier grotesque is safely behind bars in Deep Hall, with its modern replacement guarding Front Quad from over the doorway to Hall.